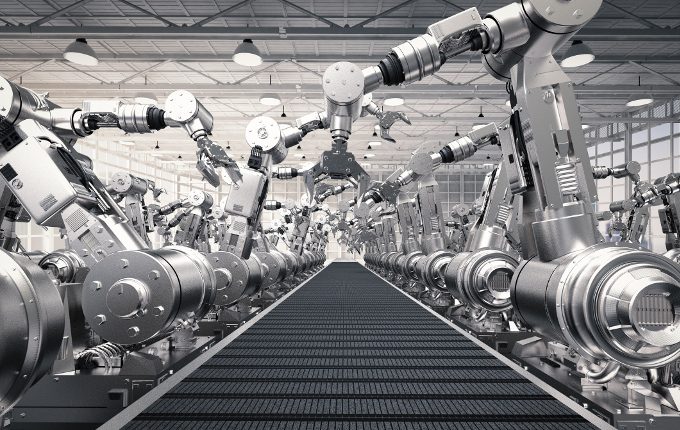

Speculation has been running rampant as to the potential ramifications of the current pace of adoption of automation technologies in the workplace.

From one extreme to the other, studies have projected that as much as half of all jobs are at risk of being fully automated over the next few decades, while others have estimated that only 5 per cent of jobs are at risk.

But such reports often have a very broad focus, and given that the impact is unlikely to be uniform globally, it is important to consider the potential implications at a more granular level. For example, what are the potentially unique ramifications for emerging market countries?

When robots were first introduced into industrial workplaces, the cost of them was high and the payback period was long. It was difficult for companies to rationalise the expense of robots when labour costs were considerably cheaper. The divergence between labour costs and robot costs was even greater in emerging market countries because of their relatively low wages.

The extent of the already ongoing shift in low-cost manufacturing from China to the world’s poorer emerging market countries may be much less extensive in scope if automation continues to become a more appealing investment

However, as emerging markets continue to develop, there will be continued upward pressure on wages. This is a standard phenomenon for most developing countries because of the positive impact that development has on the standard of living.

China is a great example of this, given the strong manufacturing-driven growth that it has experienced over the last decade. Many multinational companies have capitalised on the country’s historically low wage costs by establishing their manufacturing businesses in China.

As a result, the country’s annual growth rate has averaged just north of 8 per cent since the end of the financial crisis and the minimum wage levels in some of the country’s manufacturing centres have recorded annual double digit increases over the past decade.

While the higher wages are beneficial for Chinese workers, they are also a detractor from doing business in China altogether. Companies that rely on human labour bear the brunt of the improved standard of living. The expected result will be for Chinese manufacturers to adopt automation technologies more quickly to reduce human labour costs.

As robots get cheaper (as most things do once they are made in higher volumes and adopted more broadly) and wage inflation pressures mount in emerging markets, labour costs and robot costs will converge. This makes robots increasingly attractive, which we expect would cause a quicker and more widespread adoption of automation technologies.

As robots get cheaper and wage inflation pressures mount in emerging markets, labour costs and robot costs will converge

Ignore the increasing attractiveness of automation for a moment. Increasing wages as a result of strong economic growth could cause multinationals to reconsider the location of their large manufacturing operations.

This has already started to a certain extent, with many multinationals moving their operations away from China to countries with cheaper labour, Bangladesh and Myanmar for example.

Other countries in Southeast Asia as well as many in Africa have also been expected to benefit because of their relatively low wage costs, fast-growing working-age populations and improving infrastructure.

The extent of the already ongoing shift in low-cost manufacturing from China to the world’s poorer emerging market countries may be much less extensive in scope if automation continues to become a more appealing investment in terms of its falling cost and improving efficiency.

If the cost of human labour and the cost of automation converge, such emerging market countries may be too late to the cheap manufacturing party. Companies will opt to automate rather than pay for human labour.

In this scenario, the countries that are most desperate for strong economic growth would miss out on all that being a manufacturing hub has to offer. Job creation in these countries would be expected to be poor, particularly given their ballooning working age populations. Wage inflation would stay flat, exacerbating the already high levels of poverty.

Another drawback would be that these emerging market economies will remain relatively undiversified. They are often already highly exposed to threats such as plummeting commodity prices or the implications that weather patterns can have on agricultural output. If the adoption of automation causes multinationals to bypass these countries altogether, it would leave them highly exposed to such risks.

Emerging market countries that have been positioning themselves to be the next great manufacturing centre may need to reconsider their options and shift focus.

Developed market countries have benefited from the cheap manufacturing costs in emerging market countries for quite some time as they have imported cheap goods and services from such countries. Automation could allow developed market countries to produce said goods and services far more cheaply, eliminating entirely the need for cheap manufacturing hubs, such as the one in China.

Additionally, most patents for artificial intelligence and robots are owned by developers in developed countries, so if the technologies do cause a surge in productivity, the developed countries would be expected to benefit more than emerging markets.

This would be very detrimental for the developing world that has relied on the exports of the cheap goods and services that they produce for their economic growth over the past several decades.

Ultimately, the extent of the adoption of automation in the global workplace, and who stands to benefit the most and who will be most negatively impacted, is unlikely to be known anytime soon. That said, emerging market countries that have been positioning themselves to be the next great manufacturing centre may need to reconsider their options and shift focus.

In practice, this may result in being more domestically focused, particularly on services sectors, for instance, tourism and health care where disruption through automation will be more difficult and jobs can be undertaken by low cost and often relatively unskilled labour.

Nicole McMillan is a Senior Adviser at Whitehelm Capital.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.