In this brief guide, we discuss some of the characteristics and peculiarities of the Australian pension fund industry and how this influences the way these funds invest their money.

Our first guide to Pension Funds in Australia was published in 2020 and a lot has happened since then. The Your Future, Your Super (YFYS) performance test didn’t exist yet, Comprehensive Income Products for Retirement (CIPRs) were still a thing and the Australian Retirement Trust still had to form.

Time for an update.

Pension funds in Australia are referred to as superannuation funds. The term superannuation didn’t always have a positive meaning, as in the 1600s the word ‘superannuate’ meant ‘to be rendered obsolete’.

Originally, the word is derived from the Latin superannate, which means ‘more than a year old’ and was used for cattle. It wasn’t until the mid-1700s that it gradually took on the meaning of ‘retired on account of old age’.

The Origin of Australia’s Pension System

The year 1992 marks the birth of Australia’s modern pension system, which has grown to $3.5 trillion as of June 2023. That year compulsory superannuation was introduced in Australia under a series of reforms that included the superannuation guarantee, which established mandatory contributions by employers.

Although there are still a number of defined benefit schemes in existence, most of them closed, the 1992 system is a defined contribution scheme, where the employer pays a set rate of an employee’s salary into an individual account and the member bears all of the investment risk.

The employer contribution rate was 9.5 per cent since 1 July 2014, but has slowly been increased to 11 per cent currently. The rate is scheduled to increase to 12 per cent on 1 July 2025.

Contributions receive a favourable taxation treatment and are taxed at 15 per cent, which is significantly lower than the net average tax rate of 23 per cent that workers paid on their income in 2022.

Australia also maintains a means-tested age pension paid for out of general tax revenue.

Superannuation funds did exist before 1992, but they were available to less than half of the working population and had many constraints.

In the 2012 book, ‘A Super History: How Australia’s $1 trillion superannuation industry was made’ by Christine St Anne, union organiser Greg Sword says that many funds required workers to remain with a company for 35 to 40 years to be eligible for superannuation payments. Something that wasn’t realistic even then.

Dissatisfaction with the arrangements led Sword to help establish pension fund LUCRF in 1978, of which he became the founding Chief Executive Officer. He resigned in 2014.

The seeds for the current system were sown in 1983, when the government reached a deal with trade unions on wage increases. The government would allow wages to be increased by 3 per cent, but in an effort to curb inflation, workers would not be able to spend this 3 per cent, but instead it would be paid out in the form of contributions into a superannuation fund.

Types of Funds

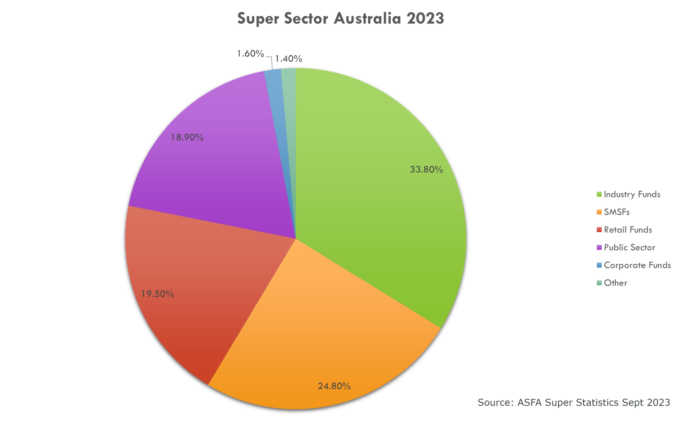

Australian pension funds can be divided into five groups: industry, retail, corporate, public and self-managed super funds.

Although many funds are now open to all workers, industry funds find their origins in catering to specific sections of the workforce and are usually associated with a particular union. They often have union representatives on their boards, under a system called equal representation, where half of trustee directors are appointed by employer representatives and half by member representatives. In more recent years, there have been calls for at least a third of board members to be independent, while also increasing the number of female directors on the board.

The majority of industry funds are set up as non-profit or profit-to-members organisations, enabling them to set competitive fees. They can vary from relatively small funds in terms of assets under management to very large.

There have been a number of large mergers among industry funds, since the previous version of this guide three years ago. SunSuper and QSuper merged to become the Australian Retirement Trust (ART), while First State Super and VicSuper merged to become Aware Super.

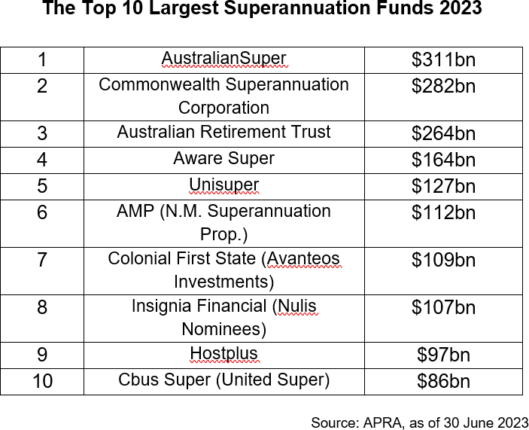

AustralianSuper is still the largest industry fund, as well as the largest pension fund in Australia overall, at $300 billion in assets under management and with more than 3.2 million members as of 30 June 2023.

Retail funds or master trusts are commercial pension funds, which historically were run by banks or wealth management businesses. They often had the benefit of a large army of financial planners, which formed a source of referrals and also provided a sticky client base.

But in recent years, banks have been selling off their master trusts, along with its wealth management operations. ANZ sold its Onepath business to IOOF in 2020, while NAB divested MLC a year later also to IOOF. The merged businesses have been rebranded as Insignia Financial.

Colonial First State’s super business was sold to private equity firm KKR in 2021, although the Commonwealth Bank of Australia retained a stake in the business. Westpac sold its BT Financial superannuation business to Mercer in April 2023.

Corporate funds have been on a sharp decline in Australia as companies have found it increasingly harder to compete with the larger and more sophisticated industry funds. In recent years, many companies, including mining giants BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto, have outsourced their corporate funds or disbanded them altogether.

Public sector funds are for government employees and unlike most pension funds, some employers contribute more than the 11 per cent minimum. For example, members of the Australian public service receive 15.4 per cent in superannuation contributions.

TCorp, the asset management arm of the state of New South Wales, is one of the larger institutional investors that looks after the pensions of public servants. It is the product of the merger of several public organisations, including workers’ compensation schemes, and has $106 billion in assets under management.

Finally, self-managed super funds are small funds that can have no more than six members. Before 1 July 2021, these funds were limited to four members, but since then they can have six.

They are often set up for taxation purposes or by people who want to have greater control over their investments, including high-net worth individuals and their families. The average balance is around $1.5 million as at 30 June 2021, but they can be as large as several tens of millions of dollars. The median size is a little over $825,000.

Despite their small average size, this sector makes up 25 per cent of all pension assets in Australia.

Peer Risk and Asset Allocation

Superannuation funds in Australia offer members a menu of investment options that they can choose from, depending on their risk appetite and circumstances. But all funds need to have a default option, called MySuper. Most MySuper products take the shape of a balanced fund, with an asset allocation of between 60 per cent to 75 per cent to growth assets, including equities, and the remainder defensive assets.

A number of providers have opted to offer life-cycle options, which automatically adjust the asset allocation and have more defensive exposures as the member grows older.

Pension funds in Australia are very sensitive to peer performance and as a result many have similar asset allocation profiles. This is partly because members are able to switch their pension money between funds within 30 days, the so-called ‘Choice’ regime.

But it is also the result of the defined contribution system, where members have their own individual account and see what their investments have done that year, unlike defined benefit funds where assets are pooled and paid out according to actuarial estimates.

More recently, new regulations were introduced under the ‘Your Future, Your Super’ regime, which includes the publication of an annual performance test by the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA). This test compares a fund’s asset allocation to a basket of indices to see if, and how much, a fund adds value. The test also takes into account investment costs and administrative fees, and ranks funds in a league table.

Although it is meant to hold funds to account for both the fees they charge and the level of investment skill they possess, critics have lamented that the test only exacerbates peer risk and is not in the member’s best interest as it doesn’t pay off to take their circumstances into account.

This peer awareness also makes it harder for funds to innovate or manage risk in times of crises because, as the great economist John Maynard Keynes said, it is less dangerous “to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally”.

But proponents of the test argue that it shines a light on underperforming funds and stimulates the merger of inefficient funds into larger ones. It is no secret that the performance test was indeed a key driver behind at least some of the more recent mergers.

Although members have a choice of investment options, most super funds, especially industry funds, tend to manage the investment portfolio at a broader level, while keeping an eye on their liabilities.

Total Portfolio Approach

In more recent years, the so-called ‘total portfolio approach’ (or more awkwardly phrased ‘joined up process’) has become popular among funds, where specialists are not only responsible for their own asset classes, but are also asked to think about the risk implications of investments for the entire portfolio.

This philosophy wasn’t invented on any particular day, but it is the culmination of investment practices and philosophies being refined over many decades. Yet, the philosophy that assets can’t be viewed in isolation has been a cornerstone of Nobel laureate Harry Markowitz’ Modern Portfolio Theory since its inception.

In his seminal 1952 paper ‘Portfolio Selection’, Markowitz emphasised that investors should look at how assets correlate with each other and that a better portfolio can be constructed by selecting assets with lower correlations.

Another key moment in the development of the modern interpretation of the total portfolio approach (TPA) was when Canadian pension fund CPPIB (the Canada Pension Plan Investment Board) developed its Risk–Return–Accountability Framework around 2008, which explicitly considered trade-offs between risk and return at the fund level.

This framework laid the foundations for the idea that the total risk level of a portfolio can be budgeted into portions and then allocated to various investments.

The concept of risk budgeting was known before. A key person in the development of this concept was Richard Grinold, who, along with Ronald Kahn, wrote the 1999 book “Active Portfolio Management: A Quantitative Approach for Producing Superior Returns and Controlling Risk.” This book discussed risk budgeting as part of a broader framework of active portfolio management.

Yet, the combination of a view on total risk and the practice of risk budgeting, in the context of a reference portfolio (a paper portfolio made up of broad indices with an asset allocation that forms the starting point of investing), can be seen as one of the first true implementations of modern TPA.

In Australia, AustralianSuper, thr Future Fund (although technical not a super fund), QSuper before the merger, REST and TCorp, all implement various forms of TPA, albeit not all using a reference portfolio.

Insourcing Asset Management

Pension funds have grown rapidly since the introduction of mandatory contributions in 1992 and as they have grown, they’ve started to insource asset management functions.

This trend has been partly inspired by some of the large Canadian pension funds, but where those funds insourced the more complex and expensive asset classes of private equity and real estate, Australian funds have favoured domestic equities and fixed income as their first port of call.

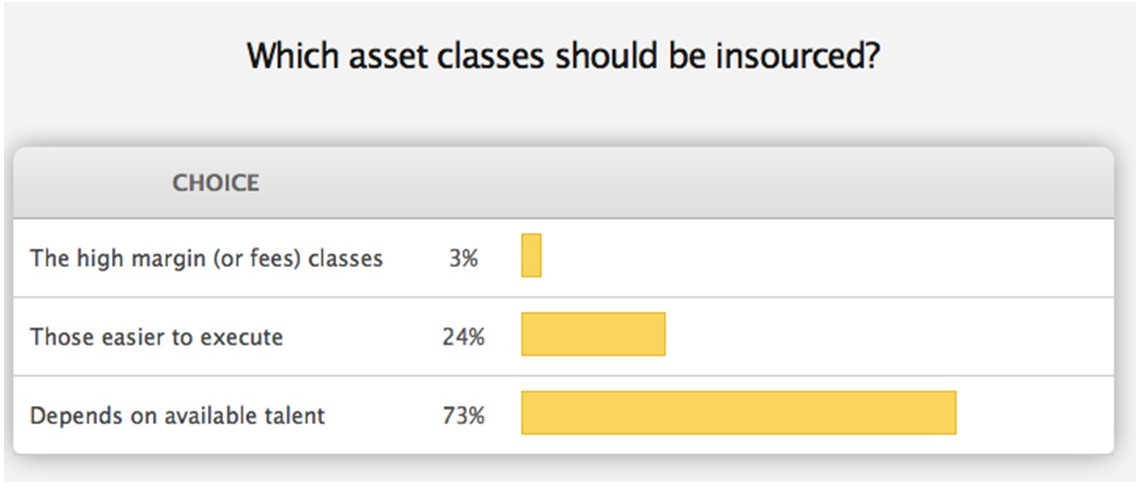

Local funds take the view that it makes sense to start with asset classes they understand and that are relatively easy to execute. But a 2016 poll by the Investment Innovation Institute [i3] showed the most important driver here was the available talent.

Source: Investment Innovation Institute [i3]

AustralianSuper has been particularly vocal on the benefits of insourcing, citing lower costs and better alignment of interests between the investment team and its members. But many funds also find they have a better grasp of price discovery and deal flow as they are closer to the market than under a fully outsourced model.

Unisuper is a fund that has run internal strategies for many years and has become particularly adept at exploiting short-term market dislocations. The fund’s investment team, led by John Pearce, runs about 80 per cent of assets in-house and they are known for backing up their views with sizeable allocations.

Questions have been raised about whether funds would have the stomach to fire their own investment teams if performance proves lacklustre, but some funds, including pension fund for the construction and real estate industry Cbus, have addressed these concerns by appointing external advisers to track performance.

Cbus is also unique in that it fully owns a property development company, Cbus Property, which operates independently and, just like any other manager, is given a mandate to fulfil. This company has been running for more than a decade and manages more than $6 billion in investments and developments in the commercial, retail and residential sectors, while it has a further $5 billion of development work underway.

Other funds have refrained from insourcing and remain fully outsourced, including Hostplus and ART. Although Ian Patrick, Chief Investment Officer of ART, left the door open to in-house management as the fund gains more assets.

TCorp has taken a different approach and has embarked on a partnership model where it seeks to have fewer relationships with managers, but makes use of the broader skill set within these firms. It also has set up partnerships with international peers, including several Canadian funds, co-investing in large infrastructure assets around the world.

Retirement

Retirement is a somewhat underdeveloped segment of the Australian pension industry. As superannuation contributions only became compulsory in 1992, the first cohort of members that have gone through the entire system have only started to retire in the past couple of years. Most existing retirement products are simply tax-adjusted versions of the accumulation products.

In recent years, super funds have started to realise the gap in their product line-up and have begun work on developing comprehensive offerings. The need to develop a retirement product is given impetus by the regulator’s introduction of the retirement covenant.

This covenant came into effect on 1 July 2022 and requires funds to publish their strategy towards developing suitable retirement solutions on their websites. The covenant has forced funds to face the issue, but it is still early days in terms of the development of relevant strategies. Funds face the difficulty of developing a mass product for what is often a highly individualised set of circumstances.

APRA conducted a survey of 16 covenants earlier in 2023 and found that there was still little progress to be found.

“Overall, there was a lack of progress and insufficient urgency from RSE licensees in embracing the retirement income covenant to improve members’ retirement outcome,” the regulator complained in a report published in July 2023.

ESG and Local Economy

Pension funds in Australia have increasingly embraced environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) considerations as important drivers in investment research, but they haven’t been at the forefront of this development in the way some European pension funds have been.

This can partly be explained by the make-up of the Australian economy. Mining and exploration form a large part of the domestic economy, with resources representing nearly 60 per cent of all export revenues. As such, environmental issues, such as climate change, have become highly politicised discussions, which has led pension funds to tread carefully around these topics.

There is also the discussion around fiduciary duty towards members. In Australia, the government has defined the purpose of its pension system as “to provide an adequate income to ensure all Australians achieve a comfortable standard of living in retirement, supplementing or substituting the Age Pension” in the Superannuation (Objective) Bill 2016.

With this description, the government has defined the primary objective of the pension system purely in financial terms and this has led many pension fund trustees to conclude that all other considerations, including ethical considerations, are secondary to this objective.

But some pension funds see sustainability not just as a moral discussion, but also as resulting in having better investment outcomes, especially over the long term. Joint efforts by regulators globally, under the watchful eye of the International Organization of Securities Commissions, have also caused APRA to urge pension funds to develop assessment frameworks to quantify the impact of climate change on investment portfolios.

In addition, increasingly more funds have committed to the carbon emissions net-zero target by 2050, which would place them in line with the Paris accord’s target to limit global warming to 1.5 degree Celsius, compared to pre-industrial levels. Some funds have also set themselves interim targets to ensure this issue isn’t simply relegated to future years.

Related to the net zero ambitions is the realisation that the transformation of the global economy to one that is powered by renewable energy requires a lot of capital for investment and superannuation funds are well-placed to be providers of this capital.

Energy transition strategies, for now, tend to focus on infrastructure assets, but as the transition gains momentum it is likely that it will affect all asset classes over time.

A key driver of the energy transition are regulations around limiting emissions. For example, European Union lawmakers are planning to ban the sale of new combustion engine cars by 2035. In the United States, the Inflation Reduction Act has committed billions of dollars to renewable energy projects.

The Australian government has also committed to the net zero 2050 target and is slowly catching up on it climate policy. In March 2023, Parliament passed legislation that requires many major polluters, including fossil fuel operations, other mines, refineries and smelters, to cut emissions intensity by five per cent a year, either through absolute cuts or by buying carbon offsets.

This legislation is intended to safeguard the government’s interim target of cutting emissions by 43 per cent by 2030, compared to 2005 levels.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.