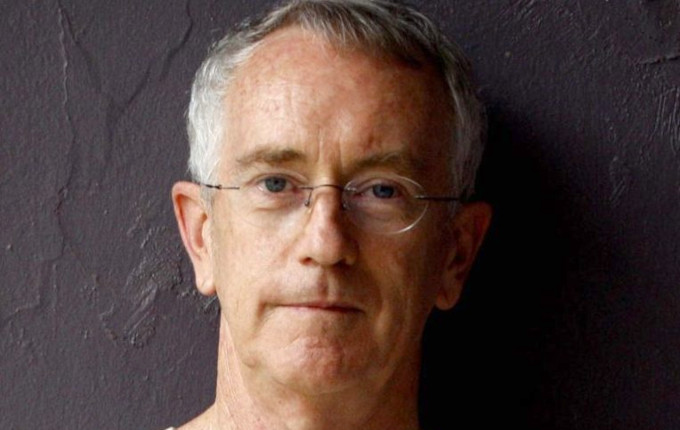

The impact of climate change on global economies has been grossly underestimated, economist Steve Keen argues.

The impact of climate change on the global economy, and in extension investment portfolios, has been significantly underestimated due to problems with widely-used economic models that assess the impact of global warming on future gross domestic product (GDP) growth.

Economist Steve Keen says these models are incomplete and often ignore current climate science research.

“Neoclassical economists are fundamentally climate change deniers. They don’t deny that it’s happening, but they deny that it matters,” Keen says in an interview with [i3] Insights.

Neoclassical economists are fundamentally climate change deniers. They don't deny that it's happening, but they deny that it matters – Steve Keen

Last month, Keen published a report for Carbon Tracker in which he explains the problems with economic climate change models.

In the report, titled “Loading the DICE against pension funds: Flawed economic thinking on climate has put your pension at risk”, Keen cites a number of economic papers that calculate the impact of global warming on economic activity.

Many of these papers find the impact of climate change on future GDP growth is rather modest, even when the temperature rises as high as six degrees. Keen says these findings are at odds with the ecological collapse that climate scientists expect from such an increase.

“There’s no way that [climate] scientists are going to imagine that human civilisation can continue with something of the order of five to 10 degrees of global warming. It’s a very, very different reaction to what you get out of the economist saying that six degrees of warming will reduce future GDP by 8.5 per cent,” he says.

He says climate change must be treated as a potentially existential threat to the economy, rather than a mere cost-benefit analysis.

“[Economists] are not talking about climate change; they’re talking about weather,” Keen says. “And you cannot extrapolate weather to climate. Weather is what you’ve got with a fixed climate. We’re talking about a complete change in the climate.

“Four degrees of warming will change the entire structure of the circulation systems of the planet and will eliminate our capacity to produce virtually anything,” he says.

It All Started With Nordhaus

Nobel Prize winner William Nordhaus was the first economist to model the impact of climate change on GDP growth. He created an integrated assessment model, the dynamic integrated climate‐economy (DICE), to assess how the economy and climate interacted.

DICE is widely used, including by asset consultants in the investment industry, and Keen shows in the report how the findings of models like these find their way into the risk assessment of local government pension funds in the United Kingdom.

The first results of DICE were published in 1992 and the model has been frequently updated since then.

The most recent update took place earlier this year and Nordhaus now estimates that if global average temperatures increase by three degrees Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels, for which Nordhaus uses the year 1765 as a reference point, annual GDP growth will be 3.12 per cent lower than if there was no impact from climate change.

At six degrees warming, GDP losses will reach 12.5 per cent a year, the DICE model predicts.

Keen says this is not in line with climate science, which expects to see severe ecological tipping points at levels well before we reach a six-degree increase.

“Nordhaus was the first economist to write on climate change, and he literally began with the statement that he assumed that 87 per cent of the American economy and, therefore, global by extrapolation, would be unaffected by climate change, because it takes place in carefully controlled environments that will be negligibly affected,” he says.

“That shows absolute ignorance about what climate change actually is. He’s basically saying climate is the weather. If your business isn’t exposed to the weather, then it’s not exposed to climate change.

“The only industries that would be affected [under the DICE model] were farming and forestry, and a bit of transport and a bit of coastal real estate. And this gives an idea of how sloppy and ignorant economists are over this issue. He even included mining as one of the industries which would be unaffected,” he says.

A key issue is that many of these integrated assessment models don’t take climate tipping points into account – the point at which the rise in temperature causes ecological processes to move to a different state or even collapse.

For example, further warming could lead to the disappearance of ice in the Arctic during the summer months. This would increase flood risk and reduce the reflectivity of the earth, which could push temperatures even higher and lead to extreme heatwaves and loss of ecosystems.

Many climate scientists anticipate a significant amount of damage to physical assets will already occur once temperatures breach the 1.5-degrees threshold, while Keen quotes a 2022 climate science paper that implies the impact of a three degree increase could be “catastrophic”.

Nordhaus is aware of the shortcomings of his model and in his 2023 update made an attempt to include data on tipping points. He uses a study on tipping points by academics Simon Dietz, James Rising, Thomas Stoerk, and Gernot Wagner from 2021, titled ‘Economic impacts of tipping points in the climate system’.

In a working paper from April this year, Nordhaus notes that “the quadratic functional form … does not reflect potential concerns about threshold damages which might appear at 1.5 or 2.0 °C warming beyond those included in the Dietz et al (2021) tipping points study”.

So they're saying that losing Arctic summer sea ice, Greenland, the West Antarctic shelf, the Amazon basin, the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, ocean methane hydrates, permafrost, and the Indian monsoon would have virtually no impact upon GDP. That is nonsense – Steve Keen

Keen thinks this tipping point study is still lacking in understanding of the impact of climate change.

“They claim that losing eight major tipping points would reduce future GDP by 1 per cent at three degrees of warming, and by 1.4 per cent at six degrees of warming,” he says.

“So they’re saying that losing Arctic summer sea ice, Greenland, the West Antarctic shelf, the Amazon basin, the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation, ocean methane hydrates, permafrost, and the Indian monsoon would have virtually no impact upon GDP. That is nonsense.”

The disconnect between economists and climate scientists will ultimately impact portfolios, Keen argues, as a sudden realisation of the scale of damage will lead to a major collapse of asset values.

Companies will start writing off the value of affected assets and governments will put restrictions on the use of fossil fuels, while auditors will do their part in writing down coal mines, coal or gas fired power stations and other oil and gas facilities, including wells, refineries, pipelines and tankers.

It is a point in time Keen calls a “Climate Change Minsky Moment”.

“Given the erroneous assumptions applied, the use of non-independent data, the lack of scenario analysis (including the widespread failure to use nonlinear damage functions other than a quadratic), and the faith invested in this work by pension funds, consultants, financial regulators, and financial markets, we believe that an unpleasant, abrupt and wealth-destroying Minsky Moment is virtually inevitable,” Keen concludes in the report.

What to do?

The outlook Keen paints for the future is a sombre one, but he does have a few suggestions for investors who are willing to listen to his arguments.

“They need to just stop using the damage functions from economists. There’s not a single paper that I’ve read in this literature on what they call the total cost of carbon – there’s about 40 of them and I’ve read them all – not one of them deserves to be published,” he says.

“They all make some crazy assumptions. Nordhaus, for example, assumes a roof will protect you from climate change and so he rules out 87 per cent of the economy being affected.”

Instead, investors would do better to look at data that is available on the cost of severe weather events in recent times. Keen points to a database maintained by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration of America (NOAA), which tracks climate events that have caused more than US$ 1 billion in damages between 1980 and now. These events and their rate of acceleration give a much better idea of the damage involved in climate change.

Keen also proposes to not only use the quadratic functions of the DICE model, but also include logistic and exponential functions, which tend to give a better sense of how tipping points might affect the economy.

“The typical quadratic [function] that economists use results in about 20 per cent of damages at six degrees of warming. The logistic [function] points to a complete elimination of the economy at six degrees, and the exponential [function] gives a complete elimination at four degrees,” he says.

“So it all comes down to how you extrapolate, and which one makes more sense in the context of tipping points, and then you can rule out the quadratic straightaway,” he says.

Starting Point

Michael Penn, Head of Climate Macro Strategy at Absolute Strategic Research, advises clients on the macroeconomic impacts of climate change. He uses three different integrated assessment models in his analysis, but agrees with Keen that these models in themselves do not provide an accurate picture.

“Really, it’s just a simulation of what might happen to the world. They take a model of the economy, take a model of the climate system, the energy system, the agriculture and water systems, and put them all together,” Penn says.

“They assume some adaptation along the way. They’ll say: ‘Okay, even if the world got really hot, we’re going to assume that humans can adapt in certain ways.’ So the impact on the economy is not going to be quite as big as it would have been if we’d seen the same amount of warming 20 or 30 years ago.

“So they will give us a good starting point. But the big problem is that these models might work for small temperature changes, but they don’t work for larger ones,” he says.

Penn thinks about tipping points in terms of what he calls a “Green Swan” event, a critical climate threshold which, once crossed, leads to large and irreversible damage. He borrows here from Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s concept of Black Swan events, which are unexpected, sudden shocks to the financial system.

“We’ve kind of looked at these tipping points and the idea that there are these kinds of events that are outside of normal econometric modelling. For example, the World Bank did a study saying: ‘Let’s assume a 70 per cent collapse in biodiversity by the year 2030. What would be the impact on the global economy if we saw something like that?’

“And the impacts were several orders higher than the regular DICE-style models would tell you. Essentially, it would be like having a global pandemic every year for the next 10 years,” he says.

The World Bank study estimated global GDP would be reduced by 2.3 per cent under this scenario of a partial collapse in biodiversity, but some countries would be much more severely impacted than others.

The problem is, if you're a portfolio manager or an asset allocator, you can't make a decision between 1 per cent of GDP or the collapse of human civilization. You have to put some kind of number and distribution on it – Michael Penn

For example, African countries would experience a reduction of almost 10 per cent in GDP, while Europe was more likely to see an impact of just 0.7 per cent.

Penn agrees with Keen that any climate change analysis needs to be complemented with current data on climate events, including wildfires, droughts and fluctuations in the thickness of Antarctic ice.

But he does see a role for integrated assessment models, such as DICE, as a starting point. “You cannot rely on it as the end point of the analysis, but let’s use them as a starting point,” he says.

“There is sometimes a bit of a gap between econometricians who will use these models to say: ‘1 per cent of GDP feels reasonable’. And then you have a group of academics, who will say that this is so outside of human understanding that we can’t put numbers on it. It’s just the collapse of civilisation.

“The problem is, if you’re a portfolio manager or an asset allocator, you can’t make a decision between 1 per cent of GDP or the collapse of human civilisation. You have to put some kind of number and distribution on it,” he says.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.