Outside of the mining and farming sectors, productivity in Australia is actually not in too bad of a shape, former RBA Governor says

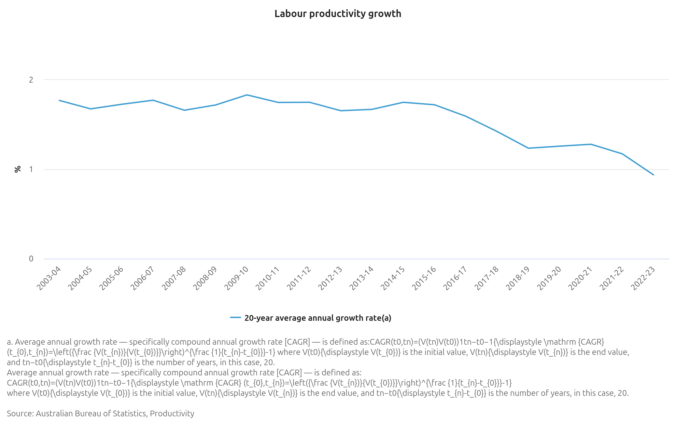

Productivity in Australia has been in decline in the last decade, to the despair of many market observers.

Australian Industry Group called Australian productivity “unhelpfully weak”, in a research note earlier this year.

Part of the lacklustre performance over the last 10 years can be attributed to the COVID-19 pandemic, but the group said productivity hadn’t picked up to the extent it expected in the years following the end of the pandemic.

AI Group warned that we can’t let productivity languish in a world that is facing increasing technological disruption, or we will risk being left behind.

But Glenn Stevens, former Governor of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) and current Chairman of Macquarie, isn’t too pessimistic about productivity in Australia.

“It’s true that in the aggregate productivity performance has been quite poor in recent years. But if you disaggregate [the data], there’s an interesting story,” Stevens said at the Frontier Advisors Annual Conference 2025 in Melbourne on Thursday.

What's happened is that mining productivity has been going down. Most of that might be in coal mining, which, I suspect, might be to do with the long run trends that are likely to happen in that sector

“Non-farming, non-mining output per hour worked has actually done fine over recent years. There was a perturbation with COVID, as there was with everything, but after that’s all out of the numbers then that [productivity] is still growing,” he said.

The decline in productivity in the mining sector might be due to structural trends in the energy sector as many countries seek to move away from fossil fuels, in favour of renewable energy.

“What’s happened is that mining productivity has been going down. Most of that might be in coal mining, which, I suspect, might be to do with the long run trends that are likely to happen in that sector,” Stevens said.

“But non-farming, non-mining has been going not too badly at all,” he said.

Market versus Non-market Economies

Productivity is generally split into market economy productivity and non-market productivity, which includes public administration, education, healthcare and social sectors. Non-market economy productivity is notoriously hard to measure, because their assets and services are not priced in a competitive market.

Take a school building, for example. These buildings are much harder to value than other forms of real estate, since they are almost never bought and sold.

Yet, the non-market economy has been growing in recent years and this will have had an effect on overall productivity, Stevens said.

“It’s a bigger share of the economy now, because of the rise of the so-called care economy,” he said.

“The question is: ‘How big a share of our total economy do we want the care economy to be? And how do we pay for that?’ Aged care, health care and disability care, these are probably good things that we want, but you have to pay for them.

“Then the onus is on the market part of the economy to be productive enough to fund what are effectively transfer payments, to pay for all those things. So that’s a challenge we face,” he said.

Boosting Productivity and the Role of the Productivity Commission

Boosting productivity is not an easy task, but Stevens said that the work of the Productivity Commission is instrumental in setting a path forwards.

“More than a decade ago, when Prime Minister Gillard had an economic summit in Brisbane I [was asked] a question in the Q&A: ‘What can we do about productivity?’

“I gave a very unpopular answer, which was: ‘We’ve got a body called the Productivity Commission. They’ve got a list of things to do. How about we get the list and do them?’,” Stevens said.

Many people took Stevens literally and asked the Commission for the list. But, of course, there wasn’t a sheet of paper with projects or items that could be simply rattled off. But the Commission did make use of the opportunity to push its agenda.

“There wasn’t a list. [But] the Chairman of the Productivity Commission … gave a speech where he wrote up a list and said: ‘Here it is’. We still haven’t done those things by and large, because they go to more competition, less regulation, more flexibility, these are things that are not politically easy to do or popular, but they’re still there,” Stevens said.

Productivity Is Inextricably Linked To Living Standards

The discussion about falling productivity is not just an academic debate, but is inextricably linked to the standard of living Australians enjoy. Although most central bankers spent their lives thinking about interest rates and inflation, it is actually productivity that is the key driver of living standards, Stevens said.

“Living standards are entirely [about] productivity. It’s not mainly; it’s entirely [about] productivity,” he said.

“It’s entirely [about] how to get more out of the stock of physical capital and human capital, know-how and productive resources, including land. How do you get more out of that to live better? It’s entirely [about] how to be more productive.

It isn't about working harder for less. It isn't that. It's more from everything by working more effectively and working out how to do better with what we have

“And it isn’t about working harder for less. It isn’t that. It’s more from everything by working more effectively and working out how to do better with what we have,” he said.

Although governments have a role in setting the right circumstances for productivity to grow, including reducing crippling regulations, ultimately governments can’t drive growth in this matter.

“Where does productivity come from? It doesn’t come from government programs. Where productivity comes from is all of us here in our businesses. How do we do this a bit better than we were doing it yesterday?

“It comes from know-how, mainly, and embodied technology.

“AI is going to be a factor there,” Stevens said.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.