A tragedy happens, not when one thing goes wrong, but when many things go wrong at the same time. Can we learn lessons from the sinking of the Titanic and apply them to our portfolios as the pandemic wreaks havoc? Teik Heng Tan explores this issue.

Much has been written about the current pandemic and the ramifications for financial markets, with market analysts drawing comparisons back to the Great Depression about a hundred years ago.

Currently caught in the centre of this calamity are the luxury cruise ships that have inadvertently become catalysts for the spread of the virus, exacerbating the health crisis.

It reminds me of another crisis that happened about a hundred years ago also involving a cruise ship – the sinking of the Titanic on 15th April 1912.

According to the engineers, the Titanic was built to stay afloat for two to three days even after encountering the worst accident at sea. This would buy enough time to wait out for rescue ships to arrive. In reality, it sank rapidly, in two and a half hours, after the collision. Why?

We could analyse this in two parts:

- That even if a crisis can’t be averted, the probability can be minimised

- That despite the crisis happening, it need not degenerate into a tragedy with significant loss of lives.

Drawing a parallel to the current situation: Much as we cannot avoid the current pandemic-induced financial crisis, can we ensure that our investment portfolios remain viable and sustain minimal loss throughout this period?

(1) Avoiding a Crisis

Ask anyone why the Titanic sank, and the unequivocal blame lies squarely on the iceberg. As analogous to a floating iceberg, the real answer lies deeper. Bruce Ismay, Chairman of White Star Line, owners of Titanic, was no navigator or expert about weather and icebergs. Yet, he was keen for the ocean liner to better the record set by the Olympic in sailing across the Atlantic. Warnings about the presence of icebergs near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland were largely ignored.

Keeping to schedule was essential. Close calls with ice were not uncommon but should not be a problem for such a large ship. After all, this was the ‘unsinkable’ ship.

How those objectives were conveyed to Capital Edward J. Smith remains unclear. That those objectives overrode the delegated authority of the captain seems likely, and whether the experienced captain had the gumption to stand up to the owners is questionable.

To what extent has passenger safety been compromised to achieve the crowning glory of steering the then largest ocean liner into New York harbour in record time?

I suspect the unclear lines of authority and governance between owner/director and operating executives, led by the captain, was an ‘accident waiting to happen’.

The robustness of the governance structure with trustees and fund executives will be sorely put to test during this period of uncertainty. Will the past obsession with league tables expose agency risks and hence flaws in decision-making?

(2) Avoiding a Tragedy

Judgement

Close to midnight on April 14th when the iceberg was spotted, First Officer William Murdoch immediately ordered the ship to be steered around the obstacle. It was too late to avoid the iceberg. Instead it caused its starboard to be side-swiped and the hull separated, allowing seawater to gush into the compartments.

According to testimony by naval architect Edward H. Wilding, the Titanic should have hit the iceberg head-on, instead of trying to avoid it.

The Titanic was built to withstand four water-tight compartments filled with water. A head-on collision will bring considerable damage to the bow, with the front two to three, or maybe four, compartments damaged and flooded. However, having the side torn out flooded six compartments simultaneously, effectively guaranteeing the sinking of the ship.

No doubt both options will have serious causalities – the technical point of difference being that a serious damage to the bow contains the better chance of the ship remaining afloat longer.

Imagine yourself driving and then spotting an obstacle in front – it’s only natural that you instinctively swerve to avoid. Unfortunately, in the case of First Officer Murdoch, his instinctive reaction to swerve did not bode well for the large ship.

The equity market fallout in early March 2020 has seen some pension fund members rushing to switch from growth assets to cash, and in so doing, achieve a false sense of safety while crystallising their losses.

Design: Risk Immunisation

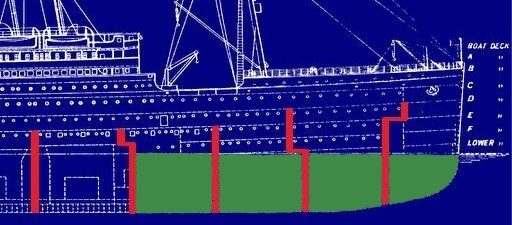

(Graphical representation for illustration purposes only)

The lower section of the Titanic had sixteen watertight compartments. This design feature meant that any flooding or fires could be isolated within the compartment and prevented from spreading.

Subsequent investigations revealed that they were only watertight when the ship was horizontal. On collision with the iceberg, as the bow of the ship began to pitch forward, water from the six initially flooded compartments began to spill over to adjacent compartments, rapidly flooding the entire ship. That only hastened the Titanic’s descent into the ocean.

Portfolio risk has often been synonymously associated with volatility. This inadequate definition will surely expose the flaws in correlation and diversification approaches during the current stressed scenarios.

Compliance vs Risk Management

The Titanic carried twenty lifeboats, which could accommodate 1,178 people, roughly a third of its passengers. At that point in time, UK’s Board of Trade only required British vessels over ten thousand tons to carry sixteen lifeboats.

Titanic was compliant with the regulations – in fact, it exceeded the minimum requirement. However, did it do enough from a risk management perspective?

With insufficient lifeboats, many passengers died of hypothermia while drifting at sea.

Regulations are often backward looking, with new ones enacted as a result of the previous crisis. Funds can pass the regulator’s inspection but lack the holistic perspective to proactively deal with new market risks on the horizon. Risk management is a mindset, much more than a box-ticking exercise.

Behavioural Bias

The inefficient deployment of lifeboats was a function of the class society that existed at that time. The life of a poor person was worth less and that, even in a disaster, the perceptual bias of class segregation firmly remained.

This bias translated into efforts to prioritise places for first class passengers ahead of second class, and so on. This constraint created further delays and meant that some lifeboats were not filled to capacity, notwithstanding the fact that there were insufficient lifeboats for everyone in the first place.

The final survivor numbers speak for themselves: Sixty-one per cent of first class passengers survived, forty-two per cent of second class and twenty-four per cent of third class.

That seventy-five per cent of female passengers survived compared to twenty per cent males is probably the only silver lining to this tragedy, showing that male chivalry was definitely alive back then.)

Some funds continue to rely solely on asset class silos to construct portfolios without due regard to their contribution to equity risk. The ongoing equity market rout will only expose the fallacy of so-called diversification or, perhaps more to the point, the false belief that correlations have sufficient stability.

Signal vs Noise

The SS Californian captained by Stanley Lord, had stopped for the night about 20 miles north of Titanic. It had encountered an ice field and decided to wait till morning before proceeding further. Before going to bed, Lord instructed his wireless operator Cyril Evans to warn any neighbouring ships about the danger.

Evans sent the message to his counterpart Jack Phillips at the Titanic, who was distracted with another message and as such, rudely told him to ‘shut up’. Having done his part, Evans switched off the wireless equipment and went to bed. That also meant that he didn’t received any distress signal from Titanic sent twenty-five minutes later.

When the crewmen at the SS Californian saw the distressed flares fired into the night sky, they attempted to alert the sleeping captain, who mis-interpreted them as some kind of routine company signals.

Had the SS Californian responded to the signal, its proximity to the crash site meant that it could have saved an untold number of lives.

The advent of big data and artificial intelligence have significantly improved our predictability of markets and correlation. However, the art and science of interpreting signals remain elusive. Funds employing dynamic or tactical asset allocation approaches may struggle to perform.

Lessons for investment management

With the coronavirus crisis decimating financial markets, can a tragic annihilation of wealth and retirement savings be avoided?

- Governance: How robust is the ‘invisible glue’ that determines the long-term viability of the business?

- Judgement: How familiar are you with the constituents of your portfolio design, their correlations and sensitivities to stress scenarios beyond regulatory requirements?

- Immunisation: Have your diversifying and protection strategies delivered in times of equity market downturn?

- Behaviour: Being contrarian is counter intuitive. How can we prevent the multitude of members switching to cash or liquidating equities during bearish moments?

- Signals: Not impossible to implement dynamically but will probably put this in the ‘too-hard basket’. Ditto tactical tilts and manoeuvres.

Luck

As the saying goes in decision-making, sometimes it’s better to be lucky than right.

The ultimate owner of White Star Lines, John Pierpont Morgan – better known today as the founder of banking giant JP Morgan – was scheduled to travel on that maiden voyage. But he became ill and cancelled at the last minute. But that is a story for another day…

_______________

I’d like to acknowledge my friend Craig Roodt, a former regulator now enjoying life as a consultant, for his contribution and inspiration on the ideas in this article.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.