What if Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters?

It was Rosabeth Moss Kanter, Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School, who formulated this question in 2010 when reflecting on the global financial crisis and the collapse of Lehman Brothers two year earlier.

Moss Kanter had just attended a World Economic Forum/Harvard Kennedy School conference where academic research into the differences in risk-taking behaviour between men and women was discussed.

The research implied women were more trustworthy, risk averse and altruistic when negotiating for other people rather than for themselves.

In thinking about how the crisis could have been avoided, Moss Kanter came up with the following hypothesis:

more women = less self-interested greed = less imprudent risk = more solid asset values = healthier balance sheets

Since then this idea has been adopted by the likes of Christine Lagarde, Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund, and Harriet Harman, a Member of the UK Parliament, who was UK Deputy Labour Leader at the time she made reference to it.

But is there any reason to think women would have acted differently if they had been in charge of the world’s largest investment banks?

You can’t assume anything about a woman based on the fact that she is a women.

The Lehman Sisters Hypothesis

It is a question that has intrigued Elizabeth Sheedy, Associate Professor at the Macquarie Applied Finance Centre, ever since the Lehman Sisters hypothesis was put forward.

“When Lehman Brothers collapsed there were a number of people who came out and said: ‘It is all the fault of the men. If there had been more women around, then we wouldn’t have these problems, or not to the same extent,'” Sheedy said at a presentation at the Macquarie Applied Finance Centre in Sydney last month.

“I always thought that was a fascinating idea. It is based on a very well-known research finding that, on average, women are more risk averse than men.

“But of course the crucial words there are ‘on average’.

“Men and women come in all shapes and sizes and the problem I always had with the Lehman Sisters hypothesis is that it assumes that the women working in banks are going to conform to these gender stereotypes.

“It comes down to the question: Are the women in banks – in particular the ones at the more senior level and therefore likely to be more influential – typical women?”

The Study

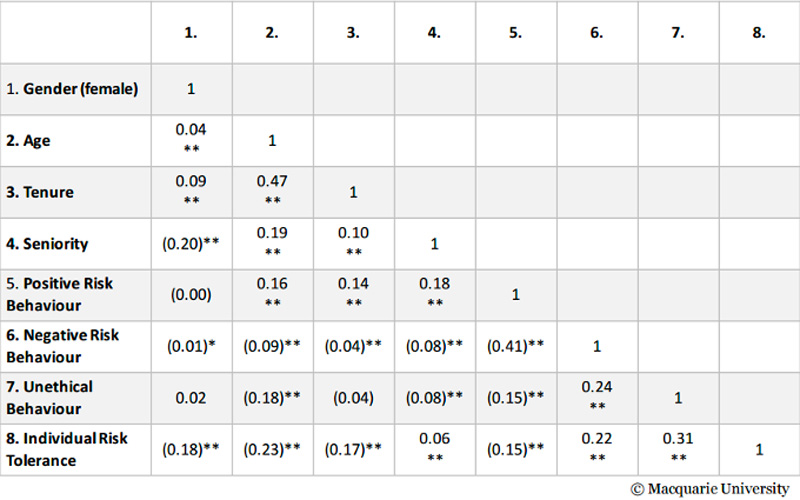

In 2014, Sheedy was involved in a major study looking at risk culture in large banks. As a result of that study, she collected a data set that included more than 30,000 surveyed responses from staff in 10 different banks in Canada, Australia and the UK.

She set out to determine if the finding that women, on average, have a lower risk tolerance than men also translated to better risk management behaviour in a corporate setting.

“This is a study where we are looking at whether demographics has anything to do with good risk behaviour,” she said.

“We are looking for people who are willing to speak up, who will challenge the policies if they think they are inappropriate. It is a mixture of having the ability to comply with policy, but also to question it.

“It is very difficult to get people to admit to non-compliance to a survey in the workplace, so that means you have to be very careful how you word survey questions. We were working with a psychologist to make sure we got these survey questions right.”

The Results

The results of this new study are remarkable. On one hand, the study confirmed the earlier findings by other researchers that women, on average, are more risk averse on individual risk metrics.

But on the other hand, it showed there is no correlation between gender and good risk management behaviour.

“If we look at the relationship between gender and individual risk tolerance, there is quite a strong gender effect: females are more risk averse on average in my data set,” Sheedy said.

“[But] if we look at the correlation between gender and risk behaviour, we can see a zero. There is nothing there.”

She also noticed something else: the influence of seniority on risk tolerance.

“Gender doesn’t give you that much information about risk tolerance in banks, but it becomes really interesting when you break it down by seniority,” she said.

“At the lowest level, you can see there is quite a clear distinction between female and male [risk tolerance]. By the time you get up to senior management, the distributions almost exactly overlap. What is that telling us? Basically, there is not a lot of difference between risk tolerance at the senior level.

“The females that get to senior levels of execution – whether it is because that was their personality to begin with or whether they adapted to the environment, I’m not sure – but what we are seeing is that there are certain types of women that get into senior roles in banks.”

So does this mean the collapse of Lehman Brothers might not have been prevented if there were more women in senior positions in the bank?

Well, it might and it might not have. In the end, the study shows you really can’t tell without knowing the personalities of the senior managers involved.

“You can’t assume anything about a woman based on the fact that she is a women,” Sheedy said.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.