I am often asked whether using passive investment funds is a clever idea.

My answer is always the same, “that depends.”

Depends upon what? you may ask.

Well hopefully this article will give you, dear gentle readers, a guide which encompasses my views.

Unfortunately, the last 10 years has seen very narrow markets, particularly in global equities. You either owned the Magnificent 7 or you did not. The outcome was binary. For those that are interested in the investment jargon, markets exhibited exceptionally low cross-sectional-volatility, namely most stocks went up or down uniformly.

Obviously, in an environment like that, it is hard for fundamental, even good active managers, to beat a cap weighted index. We can talk later whether this is the norm or not and whether active managers will have their day in the sun. The short answer is that on average global managers have had a very tough time beating their indices over a much longer period than just 10 years.

No surprise that investors have continued to move into passive cap-weighted strategies settling for average performance (compared to the index but better than most active managers even before fees) and low investment management fees. So much so that passive investment strategies are now over 50 per cent of total investments in global equities. To add insult to injury, the index has outperformed most so-called active managers over the past 10 years.

So where does that leave us? Are passive global equities always a clever idea or not?

My view is not that of a zealot. There is a place and a time for both active and passive investing. I also think that good managers can still add value in difficult markets and bad managers can still underperform in markets where the index is easy to beat. I know that because I have invested in some of them!

My proposition is simple.

- In markets which are large and well-researched it should be harder to beat a cap weighted index. [e.g. global equities]

- In narrow markets it should be harder to beat a cap weighted index. [ e.g. last 10 years of global equities]

- In markets which are smaller and less well-researched it should be easier to beat a cap weighted index. [ e.g. emerging market equities and small cap equities]

- In markets where the cap weighted index is flawed it should be easier to beat a cap weighted index. [ e.g. Australian small cap equities]

- And finally, in markets where the cap weighted index adds risk, one should avoid passive investing. [ e.g. credit]

So let us look at history to see if my hypothesis holds water.

Every 6 months SPIVA (S&P Index versus Active) publishes data around how active managers performed against their cap weighted benchmarks.

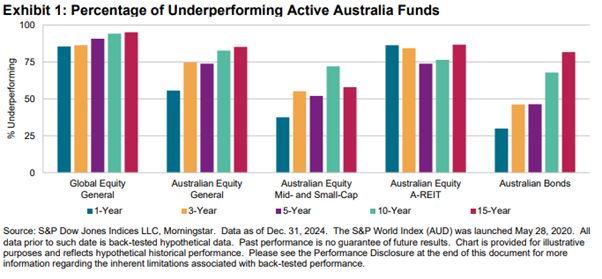

Here is the latest SPIVA data set, December 2024.

In the chart above, the higher the bars, the more the index won. (and vice versa)

This data suggests that it is hard to beat the index in global equities, results are mixed in Australian property trusts and Australian equities and investors have a good chance of beating the index in small cap Australian equities and Australian bonds.

Is that because managers are better in small caps and bonds? Clearly not!

In the case of Australian small caps, the index construction is poor and it is easy to beat the index as it contains property trusts and low-quality miners. Even a Jimmy Numnuts should be able to outperform the small ordinaries index!

My assertion that it is easy to beat a small cap index is backed up by one trail-blazing Aussie small cap manager at the pinnacle of performance that sets its performance-based fee hurdle at 2 per cent above the benchmark.

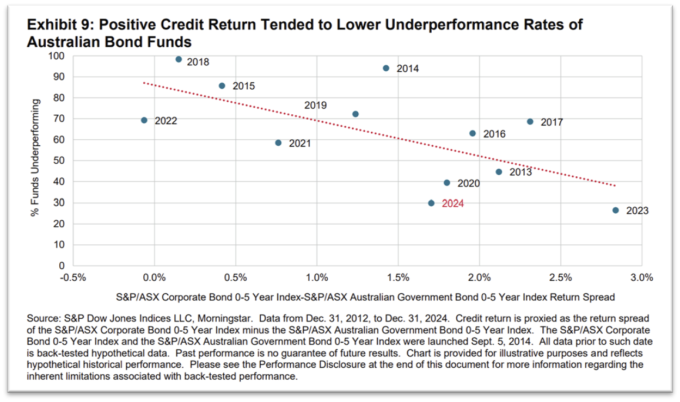

My assertion that it is easy to beat the composite bonds index is backed up by two facts.

Firstly, that there are ETFs that achieve the same performance as leading bond managers, at less than half the MER and with simple structural rules such as an overweight to duration and lower grade credit. (hello CDS)

This was also explicitly acknowledged by SPIVA in its latest report.

But why do advisers and consultants not have the same message as me? Why do they persist in allocating to active managers in all strategies, all of the time?

Maybe because they all have similar asset allocations and they are only able to differentiate themselves by choosing different managers?

Maybe because active managers buy better footy tickets?

Maybe because they and their clients want to believe that active management always wins?

Maybe because there are commercial reasons for selecting active managers?

Anyway, where does that leave us? Here are my predictions and comments.

- Allocating to Australian small caps or emerging markets equities does increase the chance of outperforming benchmarks. But make sure the outperformance justifies the high fees and consider the performance of these sub-sectors against broader benchmarks. E.g. has allocating to higher risk, higher fee strategies like Australian small caps beaten the ASX200? E.g. has allocating to higher risk, higher fee strategies like emerging markets equities beaten the MSCI All Countries World Index?

In both cases has the net alpha offset the fact the Small Ords and MSCI-EM have over 10 years of underperformance? - By all means allocate to good global equities managers if you believe that they can add value after fees but be less active in large-cap global equities than other asset sectors

- Rarely use an index for credit. Credit indices were never designed to be a benchmark. This is because more risky corporates issue more debt and thus credit indices can become over-exposed to poor credit quality. I often describe passive investing in credit as akin to providing drugs to addicts.

- By all means allocate to good fixed interest managers if you believe that they can add value after fees but be discerning and do not accept that the addition of default risk credit is more than a simple implementation.

- Rarely use active managers in bonds. My research indicates that the record of bonds managers in duration management, yield curve strategies and sector rotation is nothing to write home about. If you just want an extra 1 per cent of credit spread, this can be achieved using a low-cost ETF.

- Always compare the performance of any manager that purports to be active and asks for active fees against not just a broad benchmark but against thematic and smart-beta ETFs. If it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, then by any metrics it is a one-trick pony. (how is that for mixed metaphors) Just maybe, managers are really doing something that is more akin to beta than alpha.

- Always look at risk as part of any analysis. Recent events have demonstrated that whilst the rising tide lifted all boats (well, tech stocks and credit boats in particular) these same strategies were exposed when the tide went out. It is all about risk going forward. Buying assets where the prospective return does not outweigh the risk is a recipe for disaster. Vive la revolution!

Michael Block is Chief Investment Officer of Bellmont Securities. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of their employer or of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3].

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.