Welcome to part three, the final part of my attempt to take up the Charlie Munger challenge. In case you’ve forgotten, the challenge was for me, an active investor, to argue the case for indexing better than a passive investor.

The reasons for indexing that we considered in part one left us cold. They’re not convincing because they don’t apply in a lot of circumstances. In part two, we got a little warmer, focusing on the conflict between the activity of investing and investing as a business. Here in part 3, we get red hot, focusing on the strongest reasons for indexing. They are:

- You can’t control your behaviour. For example, you are impatient, you follow the herd or you don’t really know what you’re doing.

- Indexing will help you to outperform 60-90 per cent of your competitors because they are almost certain to behave badly (even if you don’t).

- Indexing makes fewer decisions and therefore fewer mistakes.

- Cost matters more than ever in a low return environment.

- The paradox of skill.

- You get to spend more time thinking about the really important stuff, such as objectives, asset allocation and education.

1. You can’t control your behaviour. For example, you are impatient, you follow the herd or you don’t really know what you’re doing.

There’s a reason why Warren Buffett once said that investing ‘is simple but not easy’: our behaviour.

Investing involves making decisions about the future, with incomplete information and in the face of uncertainty. Can you think of a worse environment in which to make decisions with long-term consequences? I can’t.

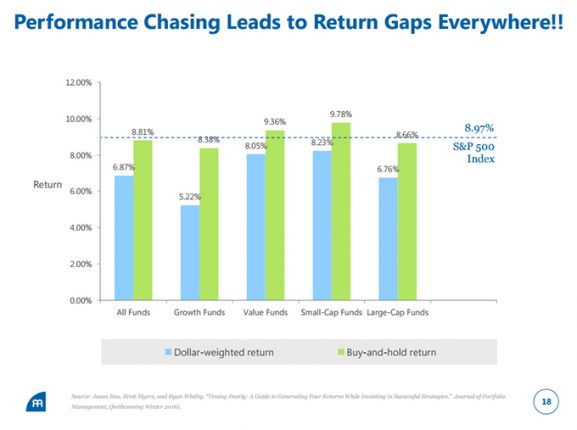

There is considerable evidence that most investors can’t control their behaviour. For example, in an earlier post, I considered the paper: Timing Poorly: A Guide to Generating Poor Returns While Investing in Successful Strategies, written by Jason Hsu, Brett Myers and Ryan Whitby.

The authors used the CRSP Survivorship-Bias-free US Mutual Fund Database to investigate the behaviour of investors across 18,665 mutual funds from 1991 through to 2013.

They compared each fund’s time-weighted return with its dollar-weighted return. The return gap or the difference between dollar-weighted returns and time-weighted returns is one way to measure the skill of mutual fund investors in picking the right mutual fund at the right time. Here’s what they found:

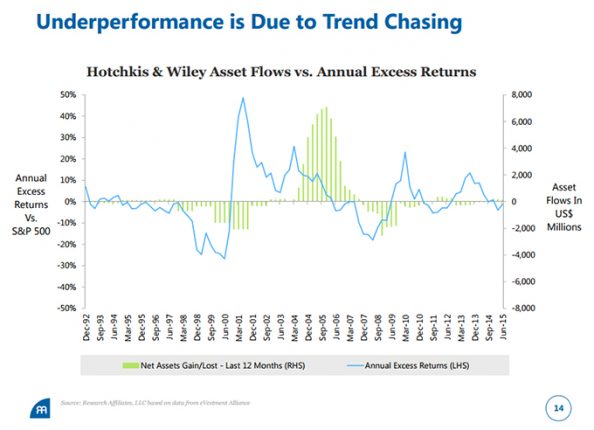

Why does this happen? Performance chasing. There’s no better illustration of this than the chart below.

Hsu, Myers and Whitby provide the example of Hotchkis & Wiley in a presentation summarising the results of their paper. As you can see in the chart above, fund flows clearly follow performance.

Yes, most mutual funds are owned by retail investors. But institutional investors shouldn’t get too cocky. The evidence suggests that they are no better than individual investors when it comes to investing in active strategies.

An earlier post considered the research of Amit Goyal and Sunil Wahal, who compiled a unique database of 8,755 hiring decisions by 3,417 plan sponsors that delegate $627 billion in mandates between 1994 and 2003.

“To summarize, we find that plan sponsors hire investment managers after superior performance but on average, post-hiring excess returns are zero. Plan sponsors fire investment managers for many reasons, including but not exclusively for underperformance. But, post-firing excess returns are frequently positive and sometimes statistically significant. Our sample of round-trips shows that if plan sponsors had stayed with fired investment managers, their excess returns would be no different from those actually delivered by newly hired managers.”

What never ceases to amaze me is how everyone seems to forget that the ‘loser’ that they’re firing was once a ‘winner’. Nobody hires a loser, so they had to be a winner. Logically, if they’ve gone from winner to loser, what’s to stop today’s winner from becoming tomorrow’s loser?

What about investment consultants? They are no better. For example, here’s a quote from a paper by Tim Jenkinson, Howard Jones, and Jose Vicente Martinez, three researchers from Oxford’s SaΪd Business School.

“We examine the aggregate recommendations of consultants with a share of over 90 per cent of the US consulting market. We find that consultants’ recommendations of funds are driven largely by soft factors, rather than the funds’ past performance, and that their recommendations have a very significant effect on fund flows, but we find no evidence that these recommendations add value to plan sponsors.”

Ouch! It seems that all of us fall into the trap of over-estimating our abilities. This shouldn’t come as a surprise as it’s a pattern that we see in many areas of our lives. Take driving as an example.

Ask most people to rate themselves as a driver and most will rate their driving skill as above average (7/10), even though it’s mathematically impossible! Ask them how other people would rate them, and the score will be 10 per cent lower. Ask them to explain the difference between the two scores and they’ll explain that the criteria that they use to assess driving skill are different.

Most of us fall into the trap of looking at the evidence and deciding that it applies to everyone else but doesn’t apply to us.

The only way to minimise the impact of behavioural biases is to create a governance structure and an investment strategy designed to promote good decision-making. But this is very difficult to do when investing on behalf of someone else (see part two of this series).

Very few succeed. Which is why one CIO even went as far as saying that his mum beats most CIOs. Sadly, institutional decision-making usually resembles the parable of the seven fund managers.

2. Indexing will help you to outperform 60-90 per cent of your competitors because they are almost certain to behave badly (even if you don’t).

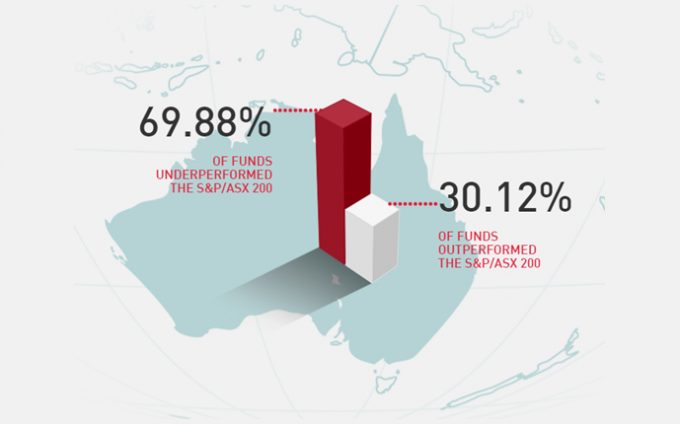

Don’t take my word for it, take a look at the Standard and Poor’s SPIVA survey results. As the image below shows, almost 70 per cent of Australian equity fund managers have underperformed over the last five years.

The evidence raises an interesting possibility. Even if you do have skill in selecting active investment strategies, most of your competitors don’t. So, it’s possible to outperform at a lower cost and with none of the behavioural pitfalls by indexing.

3. Indexing makes fewer decisions and therefore fewer mistakes.

Back in 2015 when I attended the Columbia Business School Value Investing Program, Professor Bruce Greenwald began by asking the class what we thought the fundamental rule of investing is. After considering several responses from the class, the professor gave us his fundamental rule:

“Every trade has a buyer and a seller and one of you is wrong.” He explained that it was our job to use a strategy and a process that ‘puts you on the right side of the trade’ more often than not.

This is a sobering thought. The burden to be on the right side of the trade rests with the active investor. In contrast, indexing:

- Benefits from the positive skew (point 8) of the stock market.

- Does the exact opposite (i.e. buys winners and sells losers) of most investors suffering from the disposition effect.

- Has lower turnover and therefore lower transaction costs.

- Realises fewer taxable gains.

These are some of the headwinds that active strategies have to overcome.

4. Cost matters more than ever before in a low return environment.

Let’s assume that the expected return for the stock market is 10 per cent. Beating the market by 2 per cent (or delivering a 12 per cent return) requires that a fund manager be 20 per cent better than the market net of trading costs, and management fees. This means that a fund manager has to generate a gross return at least 25-30 per cent higher than the market.

What if the expected return was only 5 per cent? Achieving 2 per cent outperformance now requires a return that is 40 per cent higher than the market net of costs and fees. It’s probably closer to 50 per cent gross of trading costs and management fees.

In this example, a fund manager has to be twice as good to deliver the same level of outperformance. Lots of luck.

Active management strongly favours the fund manager over the client. Perhaps the simplest explanation why can be found in Charley Ellis’ must read book: Winning the Loser’s Game, Seventh Edition: Timeless Strategies for Successful Investing. I’ll let Charley explain:

“If a fund manager says the fee is ‘only 1 per cent’, he or she means 1 per cent of assets. But if you get an average annual rate of return as high as 9 per cent, you might say that the manager’s fee is closer to 10 per cent. Look still closer, please. You already own all the assets, and you can get 9 per cent by investing in low-cost index funds. So the fund manager can only help you by providing incremental returns – after adjusting for risk.

Can he or she really increase your returns by 200 basis points? If so, you will be taking all of the risk, and the manager’s real fee will be 50 per cent – 50 per cent of real value added. If returns are increased only by 100 basis points, the real fee will be 100 percent, and you’re still putting up all of the money and taking all of the risks. And if the manager does not add that much value – and most don’t because they can’t – your fees are on their way toward infinity.”

5. The paradox of skill.

I was introduced to the idea ‘paradox of skill’ by Michael Mauboussin, who I was lucky enough to meet back in 2015. Mauboussin is an investment thinker par excellence, which isn’t surprising if you see his collection of investment books. It is a mini Library of Congress (so jealous!).

This section from Mauboussin’s must-read paper: Looking for Easy Games; How Passive Investing Shapes Active Management explains the concept using sport as an analogy (emphasis added):

“The first is the “paradox of skill,” which says that luck can contribute more to an outcome of an activity even as skill improves. The essential insight is the consideration of absolute and relative skill. Absolute skill has improved in nearly all domains of human performance. This is readily evident in athletics, especially when results are measured versus the clock. For example, on average elite athletes run and swim faster than ever before. The reasons for this improvement include a larger population of competitors, better training techniques, enhanced nutrition, and more refined coaching.

Skill in investing has followed the same course as sports. Today’s professional investors are better trained, have greater access to information, can rely on better theory, and have more computing power than their predecessors. If an investor with today’s capabilities were to travel back to the 1960s, he or she could run circles around the competition.

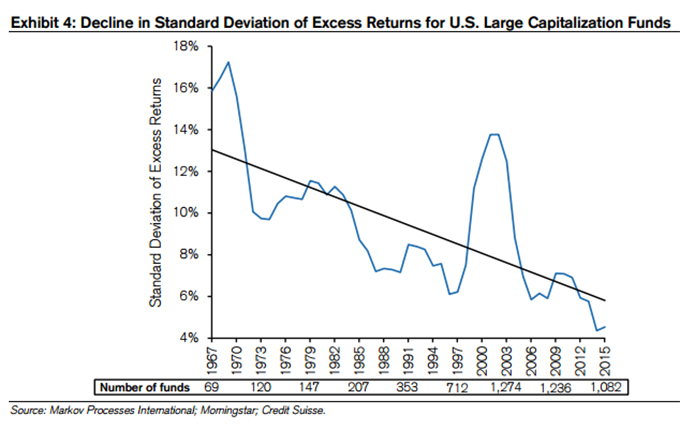

The key to the paradox is that relative skill has been shrinking in most realms. Said differently, a decline in relative skill means the difference between the best and the average participant is less today than it was in the past. Stephen Jay Gould, a biologist at Harvard, made this point with batting average in Major League Baseball: while the mean batting average has remained relatively stable over time, the standard deviation has steadily declined. The last player to sustain a batting average in excess of .400 for a full season did so in 1941.

Exhibit 4 extends the standard deviation of excess returns from exhibit 3 back to the early 1960s. The reduction is evident, with the notable deviation during the dot-com period. The results for hedge funds demonstrate a similar pattern. This is the outcome you expect in a market that is largely efficient.”

What’s not in the quote above that we discussed back in 2015 is this: as the overall skill level improves, it’s the weakest players that leave the game. This means that the remaining players are left having to compete harder to win.

How does this apply to active management? Passive investors don’t play the game. This leaves active investors to fight it out for what’s left of an ever-shrinking slice of the investment pie as investors flock to indexing. This forces the weakest players out of the game, making it even harder for those that remain to outperform the market. Reminds me of the 1986 film Highlander (“there can only be one”).

6. You get to spend more time thinking about the really important stuff, such as objectives, asset allocation and education.

Why do we universally acknowledge the importance of asset allocation and yet spend the majority of our time picking managers? Why do we pay an active fund manager, who manages a small slice of our portfolio, multiples of what we pay an asset consultant to provide strategic advice over the entire portfolio?

Wouldn’t it be better to spend the time understanding our investment goals and setting realistic objectives? If we’re investing for others, wouldn’t their interests be better served if we spent more time educating them about their investments? After all, it’s their money.

Conclusion

The active vs passive decision depends on many factors, most of which are stacked against active management. This is not because markets are efficient and can’t be beaten. Nor is it due to a lack of skill.

Active management disappoints for two main reasons. Firstly, intermediaries have put their interests above those of their clients. How else do you explain an industry where the client risks their capital and the fund manager collects the majority of the added value?

Secondly, the all-too-human response of their individual investors and fiduciaries to uncertainty. For example, short-term performance chasing and paying for useless advice from experts mean the beneficiaries hardly ever receive the returns that they’re due.

I’d like to finish these series of opinion pieces on a positive note. Here are five suggestions on how to make active management more successful:

- Honest self-appraisal. Go back and look at your hiring and firing decisions. Is there a pattern of hiring yesterday’s winner only to sack them as tomorrow’s loser? If so, why do you think the next fund manager will be different? Be honest enough to admit that you/your institution might not be cut out for active management. There’s no shame in knowing your limitations. After all, you’re likely to do better than the majority still stuck in denial.

- A genuine long-term focus. Anybody who says that they’re a long-term investor but who habitually compares monthly performance to peers or a benchmark is fooling themselves. Nothing good can ever come from it.

- Prioritise. Some markets are harder to beat than others. If you are going to be active, spend your money where it’s more likely to pay off.

- Incentives matter. Look for fee arrangements that promote a long-term relationship and incentivise both the fund manager and the client to behave correctly. Innovative fee structures such as long-term mandates are a good start.

- Behaviour persists, performance doesn’t. When assessing fund managers look at what they do and why, not their results. If a fund manager makes good decisions, their results will on average, over the long -term take care of themselves. Behaviour is also far more persistent (we are creatures of habit) and easier to identify if you know what to look for.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.