CBA is one of the most expensive banks in the world and it is more than 10 per cent of the domestic equity market. Bellmont Securities’ Daniel Deverich looks at how we got here and asks the obvious question: is CBA at peak valuation?

Commonwealth Bank of Australia (CBA) has garnered much attention in the last few years as it has moved into nosebleed territory when it comes to valuation, defying almost every professional analyst’s expectations. As Australia’s largest company, this has far and wide ramifications for Australian citizens, as well as the professional money management industry as a whole.

Background: How Did We Get Here?

Banking today is different from what it was pre-global financial crisis (GFC). Whilst banks are very much perceived as safe investments today in Australia, the fact of the matter is, they have historically been highly leveraged vehicles exposed to what has traditionally been a cyclical industry (lending that came with default cycles).

There are many ways in finance to measure leverage, however, in banking, we typically look at Assets to Equity ratios, or the inverse of this, which is the equity they are forced to hold against each loan (in Australia referred to as CET1 ratios).

The reason why this is important is the more equity the regulator forces the banks to hold, the less profitable it is to lend. For example, prior to the GFC, Citibank’s Asset to Equity ratio was 40x compared to 10x today.

Whilst the Australian banks were not quite as extreme, the same holds true. The less capital a bank is required to hold, the higher the Return on Equity (ROE, or the return on loan) they receive.

After the GFC, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (the global standard setter for prudential bank regulation) recommended banks to deleverage for financial stability reasons. Following this, APRA, the Australian regulator, went on a decade-long crusade to force all domestic banks to hold more capital (or deleverage). A similar situation occurred with the Dodd-Frank Act in the US.

Why Is This Relevant Today?

Analysts often use history as a guide to compare valuations. The purpose of the background above is to explain why, in this situation, history is not totally comparable. Given the capital requirements forced on banks today, the profitability of lending is substantially less than it was 20 years ago.

CBA used to earn a 20 per cent Return on Equity (ROE), a number substantially above the cost of capital, which encouraged growth and future expansion of the balance sheet, justifying a premium multiple to book value (value of all the net loans) i.e. you would only pay more than the value of the current loans if the bank was going to grow beyond this in the future (equity markets anticipate the future).

Today, that return on equity number has fallen to 12.9 per cent, some 35 per cent lower. This number is still above the cost of capital, however, it doesn’t encourage the same level of growth, meaning the multiple to book paid should be lower.

Putting CBA’s Valuation into Context

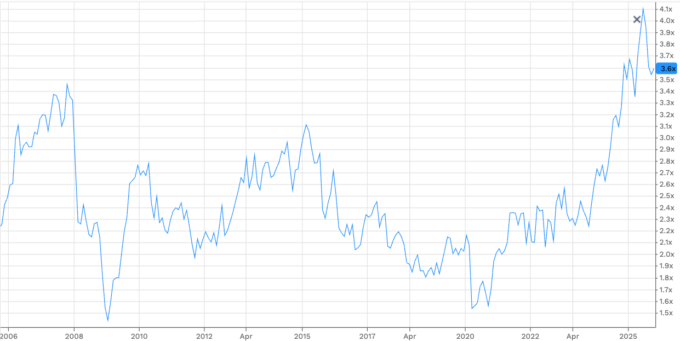

At the peak of the GFC, when everything was running hot in 2007 and with substantially looser leverage restrictions, CBA traded at a peak premium to book value of ~3.5x (i.e 3.5x the value of the net loans, also referred to as P/B ratio).

The return on equity back then, as mentioned, was ~20%. Today, CBA investors are paying ~3.6x, and receiving a 12.9 per cent return on equity, making this valuation very counterintuitive. In other words, the 3.6x today is grossly more expensive than the 3.5x pre-GFC.

Commonwealth Bank P/B Ratio 2005 – 2025

Source: Bellmont Securities

There have been multiple theories put forward as to why

1. Your Future Your Super (YFYS) regulations forcing super funds to buy

Super regulators have gone down the path of saying they can only tolerate so much underperformance, forcing funds to move closer to benchmark weights. Given the valuation dynamics explained above are well known in the investor community, super funds were mostly underweight CBA relative to its benchmark weight, which forced them to buy the stock to avoid potential underperformance if the stock kept going up.

Ah yes, the concept of career risk raises its ugly head. No worries about the clients, just got to cover our own backsides! We believe there is merit in this explanation, although it has probably run its course given these regulations were brought in four years ago and most would have covered the risk by now.

2. Passive or Index flows

We think this is a fallacy. Buying at any price from passive funds does indeed provide a marginal capital flow, however, it does that for all stocks in the index with inconsistent results on an individual security level.

3. It’s the safest yield in the market

This argument requires a little more nuance. It is undoubtedly true that the yield on CBA today is safer than it was pre-GFC. One ramification of the regulators intervening with capital requirements and stricter lending criteria is that banks have been forced down a path where they no longer lend to the lowest socioeconomic cohort of the community.

This has changed the risk of defaults on the loan book and should justify somewhat of a premium relative to history. Having said that, just because we haven’t had a default cycle, doesn’t mean that loans no longer carry default risk.

It was only in 2020 (yes, we recognise that the pandemic was a once-in-a-lifetime event) that the banks were forced to slash their dividends! The Australian economy, with the exception of the pandemic, has been in a 30-year economic expansion phase, which has had investors discounting the probability of any default cycle. Recency bias is real!

4. Capital gains issues

This certainly creates a sticky and large retail shareholder base, however, CBA is one of the most liquidly traded stocks on the ASX, with enough institutional money that could move the dial, so we don’t totally buy this argument.

5. It’s simply a better bank and deserves a premium

There is some truth to the fact that CBA is superior to the other Big Three. This argument mostly stems from the fact that CBA has a superior deposit franchise, creating a cheaper and more reliable cost of capital for them.

However, gone are the days that CBA carried a disproportionately higher ROE than the other banks. For context, NAB has an ROE of 11.1 per cent (CBA 12.9 per cent) and a P/B multiple 2.2x, a ~40 per cent lower price tag.

What are the ramifications?

● Well, if we compare CBA to NAB again, and if CBA were to normalise, then it would require a fall of 40 per cent!

● Lower passive returns, given the drag this weight could play on the benchmark over time. This would equate to about half the average market return in a given year.

● The dividend is now lower than a 10-year government bond (which is considered the benchmark for risk-free assets).

● Almost all Australians have exposure to CBA, given its 10 per cent weighting in the benchmark via personal or super holdings

What are the catalysts for normalisation?

Just ask every institutional analyst and portfolio manager – no one knows!

We do know that no bank has ever historically maintained a 3.5x P/B multiple, and we don’t expect it to this time around. When any investment is priced to perfection like this, the slightest misstep can be a catalyst.

The probability of everything going right is very low, along with the probability of the valuation being maintained. We could also look at it as an asymmetric outcome, where the upside potential seems much smaller and less probable than the downside potential!

But time will tell, as it always does when investing. I wouldn’t be the first person to call a peak in the CBA share price. It’s known as the widow maker for a reason!

Daniel Deverich is Portfolio Manager with Bellmont Securities.

_________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.