From 143 funds in 2008, to now just one left; the corporate superannuation industry in Australia has ceased to exist. But what is the end game for consolidation in the super industry?

The corporate superannuation sector in Australia has all but ceased to exist.

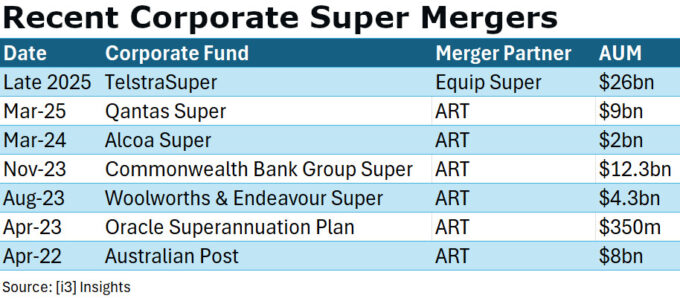

With the successor fund transfer of Qantas Super scheduled for later this month and Telstra Super later this year, APRA data shows that the corporate super fund industry will be reduced to a single fund: the ANZ Staff Superannuation (Australia) Fund.

In 2008, the sector still had 143 corporate funds.

There are a number of reasons for the demise of corporate super funds in Australia, including the desire of companies to remove the liability off their balance sheets, but regulatory pressures for smaller funds to merge has certainly contributed to the disappearance of this industry.

Some consolidation was needed. There were, and still are, some funds whose existence seems to be solely based on the desire of their board and executives to keep their jobs, rather than any perceived benefit to members.

APRA data shows that the corporate super fund industry will be reduced to a single fund

But this argument doesn’t hold true for corporate funds.

TelstraSuper has been a solid performer. It’s Balanced Fund option reported a return of 9.09 per cent over the 12 months to 28 February 2025. The option’s return since its inception on 1 January 1997 was 7.5 per cent, which means a member who started investing in 1997, on average, more than doubled their money every 10 years.

Qantas Super has been a consistent top quartile performer across all its investment options, including a glidepath approach it launched in 2015, an option which automatically reduces the level of risk as a member gets older. Its Take-off and Altitude options returned 11.8 and 10.1 per cent over the 12 months to 30 June 2024, while over a 7-year period these options returned 9.0 and 7.8 per cent respectively.

By any measure, these are well performing funds. If they feel the pressure to merge into larger entities, the question that looms large is then:

What is the end game?

If the purpose is to create an industry with only a handful of very large funds, then you can question whether this is really in the best interest of members.

Cheap But Not So Cheerful

Members are led to believe that what they want is cheap and large, but ultimately it is returns that are driving outcomes for members.

Currently, Australia’s largest super funds are still nimble enough to put their money to good use and the top 10 largest funds are all excellent performers.

But what happens when these funds start to breach the $1 trillion dollar mark which, for some, is a milestone that’s not actually too far away.

A small fund is never going to be the cheapest, but it can be a top performer by virtue of accessing niche transactions that won’t move the dial for large funds.

The pre-IPO space is a case in point. Small and mid-sized funds can participate in pre-IPO deals of $200 – 300 million and it will have a meaningful impact on their overall returns. But for larger funds this isn’t the case.

Small caps is another example. Most Australian small cap managers have a maximum capacity of circa $1 billion and, unsurprisingly, they don’t like having a single client, given the business risk this represents.

Members are led to believe that what they want is cheap and large, but ultimately it is returns that are driving outcomes for members

What about asset allocation decisions? There are examples in the Australian market, where small and mid-sized funds decided to completely exit certain asset classes, including sovereign bonds or real estate, when they determined that they weren’t being adequately compensated for investing in these assets.

Very large funds are typically less likely to be able to completely sell out of an asset class, particularly if it’s one of scale like real estate, infrastructure, or sovereign bonds.

Many industry participants believe that very large funds have less ability to implement alpha strategies in any meaningful way.

Take the Government Pension Fund of Norway. At over $1 trillion it invests predominantly passively, with some quantitative enhancements. Is this the ideal strategy for large Australian superannuation funds? Will they all become big beta players with very little scope to add alpha?

Innovation in a Semi-closed Market

You can also ask the question whether innovation is still possible in an industry ruled by a handful of large players.

First of all, entering the market for a new player will be difficult. If a $30 billion fund is already too small today in the eyes of the regulator, then how can a new player with an innovative product build up critical mass quickly enough to become a permanent player in the market?

The prospect of stagnation in the Australian superannuation industry is very real over the longer term.

Innovation is the lifeblood of any organisation and if you don’t build it into the culture of a super fund, then inevitably what you are building is a large administrative business rather than a centre of excellence for investing.

If a $30 billion fund is already too small today in the eyes of the regulator, then how can a new player with an innovative product build up critical mass quickly enough to become a permanent player in the market?

The other issue is that if Australia moves in the direction of having just a few, utility-like funds that rule the industry, we then might end up with yet another oligopoly. Australia is a relatively small economy and over the years this has resulted in several industries where power is concentrated in the hands of a few large players, with all the attendant risks this entails from a consumer perspective. The banking and supermarket sectors are obvious examples of this.

But if we get to a handful of very large super funds, will we run into the same issues of them becoming price setters?

It doesn’t have to play out like this, but the risks are real and there have been few examples where dramatically reduced competition, especially where it concerns good performing competitors, ends up being a good thing for the end consumer.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.

![Wouter Klijn, Director of Content at the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]](https://i3-invest.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Wouter-Klijn-680-679x430.jpg)