Private credit has been growing quickly in Europe in recent years, so much so that asset consultants treat it now as a core allocation in multi-asset portfolios. But did the coronavirus pandemic throw a spanner in the works for the sector? We speak to Pemberton’s Managing Partner Symon Drake-Brockman to find out.

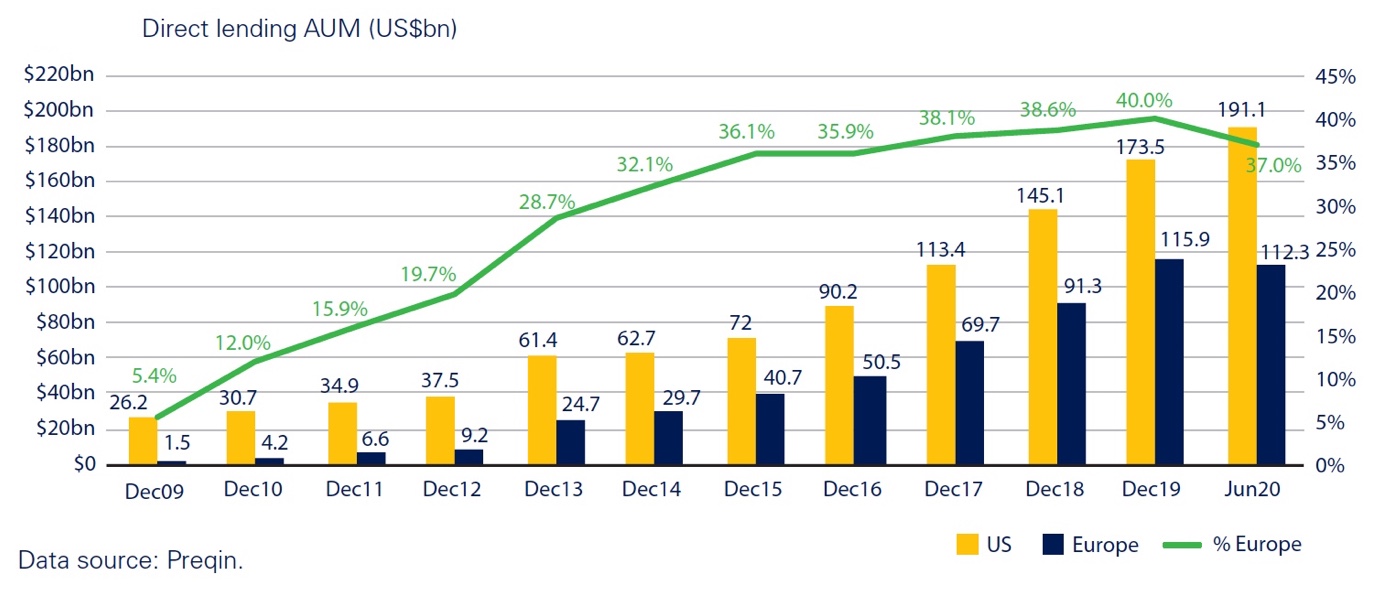

The European private debt market has expanded rapidly, especially in the years after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Direct lending, a sub-strategy within private debt, has been one of the key areas of expansion, growing from US$1.5 billion in 2009 to US$112.3 billion in June 2020, according to a study by Pemberton Asset Management, titled: ‘European Direct Lending Review and Outlook February 2021’.

Europe’s share of direct lending assets under management as a percentage of US’ and European direct lending assets combined has increased seven fold over the last decade, from 5 per cent in 2009 to 37 per cent by June 2020, according to a study by the University of Oxford-Saïd Business School, published in 2021 and written with the assistance of proprietary data from Pemberton.

But how did the sector fare as the coronavirus spread across the globe, sparking the first worldwide pandemic since the Spanish flu?

“When writing a credit paper, I don’t think I ever thought about a scenario where you had government enforced lockdowns with people having to stay at home for months at a time. So you’ve seen industries go through pretty monumental changes,” Symon Drake-Brockman, co-founder and Managing Partner of Pemberton, says in an interview with [i3] Insights.

But, perhaps surprisingly, the sector has held up well, driven by structural changes in the sector, as well as increased merger and acquisition (M&A) activity.

When writing a credit paper, I don't think I ever thought about a scenario where you had government enforced lockdowns with people having to stay at home for months at a time. So you've seen industries go through pretty monumental changes

“I think it has been a positive for the direct lending market because the market has come through this comparatively well,” Drake-Brockman says.

Since the rise of European private credit has been so rapid in recent years, some investors have expressed the concern that the sector has never been subjected to a downturn and that it was unclear how the sector would react in such circumstances.

In fact, the study by the University of Oxford-Saïd Business School made similar comments in their report:

“Through-the-cycle default data is yet to be tested in Europe, but the direct lending sector performed well in the US through the Global Financial Crisis with no higher default rate observed in non-bank vs bank lending.”

But Drake-Brockman points out that these concerns are mitigated by the fact that the sector has held up well in one of the most tumultuous periods since the GFC.

The strength of the asset class can be explained by a number of factors, he says.

“Over the last decade, the managers has been very disciplined about private equity putting in 50 per cent equity, or even 50 plus per cent, in transactions and I think those large equity buffers really made sure that in the downturn companies were in a strong financial position,” Drake-Brockman says.

He also points out that company management teams were quick to respond in conserving cash during the start of the pandemic and made sure that their businesses were well positioned to go through the downturn.

“The other key point is that we are financing different sectors today then pre-2010, when we were heavily focused in areas like manufacturing and retail. If I look at the last 20 months, we’ve done about EUR 6 – 6.5 billion, but it has been in healthcare, it has been in outsourced business services, in food and in e-commerce. Technology has changed industry and the sectors that private equity and we focus on.

“These are all growth parts of the economy rather than, I would say, some of the old economy which suffered much more through the pandemic.”

Unlike in the United States, the European private lending sector has also been able to rely on covenants in their contracts, while the US has effectively gone covenant light. This has enabled lenders to intervene in underperforming companies before the situation got out of hand.

“We saw through COVID that the European marketplace, by having covenants inside all of the documentations, was able to go to private equity pretty early on and say: ‘We’re heading to a covenant breach. Let’s sit down together and let’s work out what needs to be done’,” Drake-Brockman says.

“And I think that was very positive because private equity responded really well. We understood that this was hopefully a transient situation, but none of us knew whether it was going to be one year or two years and, therefore, we started working together in helping the companies through the process.

“We had four or five companies in our portfolio where private equity just injected equity straightaway to make sure that there was plenty of liquidity inside the businesses,” he says.

Market Growth

The private credit market went into 2020 with strong volumes levels and experienced a very active first quarter. But as COVID-19 started to roll through Europe, activity came almost to a halt in the second quarter of 2020.

Yet the news of a vaccine saw activity levels picking up again in the third quarter and by the time the fourth quarter came along lending activity was nearly back to pre-COVID levels in Europe.

In some ways, the pandemic has thrown up new opportunities in the private credit sector in Europe, as business owners reviewed the risks of remaining standalone entities and explored alternative sources of funding.

The Saïd Business School report showed that the level of ‘dry powder’ as a percentage of assets under management fell from 60 per cent to 30 per cent in 2020. Despite institutional investors allocating more capital to this sector, fund managers have been able to deploy most of that capital during the pandemic.

“The study showed that the 60 per cent dry powder came down to 30 per cent over a very short period of time and this is really going back to the growth in M&A activity and the slowdown of the banks, which meant that we were able to put the capital to work quite quickly and consistently,” Drake-Brockman says.

We think that M&A activity is going to stay the same, because one of the things that came out of COVID is you had owners of businesses who in the second quarter of last year, all of a sudden, saw the value of their businesses fall by 40 or 50 per cent, and if you're an owner who is 60 years old and this has been your life's work, then that's a pretty big shock to happen as you're heading towards retirement

“We think that M&A activity is going to stay the same, because one of the things that came out of COVID is you had owners of businesses who in the second quarter of last year, all of a sudden saw the value of their businesses fall by 40 or 50 per cent, and if you’re an owner who is 60 years old and this has been your life’s work, then that’s a pretty big shock to happen as you’re heading towards retirement.”

“Then obviously the businesses bounced back in the fourth quarter and I think that really opened up the eyes of a lot of owners to think: ‘Well, maybe I will have discussions with private equity. Maybe I will think about the opportunity set’,” he says.

This soul-searching was not limited to the older generation of whom many are close to retirement. Younger business leaders also realised that alternative sources of capital were available to them and could help them expand their operations.

“You also had young management teams who also saw the opportunity to go to private equity and say: ‘We see a huge opportunity to roll up different platforms across Europe to make a pan-European champion. Would you like to be a partner with us in the business?’

“This demographic in Europe of mid-market companies started embracing private equity and that was something we didn’t have a decade ago in Europe,” Drake-Brockman says.

Changing Regulations

The growth in private credit in Europe is partly a story of changing regulations following the GFC. The banking system was faced with tighter restrictions around capital reserves and the type of investments that banks can hold.

But there was also a clear agenda to reduce the large number of banks operating within the European Union, which ultimately has reduced the competition for corporate lending, Drake-Brockman says.

“The ECB (European Central Bank) in Europe was really trying to downsize the banking system, which had grown to be around 300 per cent of GDP, and so the central banks tried to bring banks down by forcing up capital ratios to around 12 – 14 per cent, and by the introduction of Basel III into the marketplace, which encouraged banks to hold investment grade risk, rather than non-investment grade risk,” he says.

“If you look at a country like Spain, where they used to have 70 savings banks, which are now being consolidated down to six, then that is a very dramatic change in the landscape of banking.”

“This really saw the European market for the financing of non-investment grade, mid-market companies, and particularly mid-market buyouts, shift significantly towards private equity using funds rather than banks. And as this evolved, you have seen institutional investors in Europe come into the market,” he says.

“You are now starting to see that in Italy too, while the market that is most behind is probably Germany. But the German banking industry was one of the worst affected in the GFC and you see ongoing problems at some of the large commercial banks, as well as some of the Landersbanks inside of Germany.

“As we go into Basel IV, which will come out in two years’ time, banks will move further away from this part of the market, which will open up opportunities.

“In the Saïd Business School report, they talk about the market potentially growing by 50 per cent and that was just the changes in the banking market. It did not factor in any M&A growth opportunities that we are seeing in the European markets,” he says.

A key concern about European private credit in the past was that investors had to deal with many different jurisdictions that all had their own legal peculiarities, making it difficult to scale up a private credit platform. But as the EU brought in capital markets regulations, which has significantly standardised rules around credit protection, Drake-Brockman says.

Historically, investors felt that there were tremendous differences between the United Kingdom and, for example, Spain or Italy as far as credit of protection goes. But the southern European economies have, in particular, seen massive changes in bankruptcy laws

“Historically, investors felt that there were tremendous differences between the United Kingdom and, for example, Spain or Italy as far as credit of protection goes,” he says. “But the southern European economies have, in particular, seen massive changes in bankruptcy laws.”

“Spain went through a very radical restructuring of their bankruptcy laws and which are now rather similar to those in the UK.”

“Historically, small creditors there could hold out a rather large restructuring and, therefore, be quite mischievous in bringing a solution to a company’s financial problems. But this was recently tested in the case of Abengoa (a Spanish engineering and renewables company), which involved a large restructuring.”

“When it went through the court system, the minority investors were unable to prevent the restructuring that had been agreed by the larger investors. The holdout mechanism which had been quite difficult in Spain in the past no longer applied.”

“So now you can operate in nearly all the European countries with only very minor nuances,” he says.

This article is sponsored by Pemberton Asset Management. As such, the sponsor may suggest topics for consideration, but the Investment Innovation Institute [i3] will have final control over the content.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.