Engine No 1’s victory in the proxy war against oil giant ExxonMobil has been lauded as a momentous milestone for climate change activists and ESG investors. But critics remain skeptical about the motives of Engine No. 1, with a group of academics alleging that to be a case of greenwashing.

Resounding Victory for Climate Activism?

In June 2021, Engine No. 1, owning only 0.02 per cent stake (less than US$40 million) in ExxonMobil, won an unprecedented proxy fight to install three of its four nominated directors to the board. It did so with the support of the Big 3 index providers – BlackRock, State Street Global Advisors and Vanguard – which own about 21 per cent of the stock in aggregate.

Other large institutional investors such as Californian pension CalSTRS as well as proxy advisors Glass Lewis, PIRC and Institutional Shareholder Services joined in too.

Although capitalised at about US$250 billion, ExxonMobil was financially vulnerable as a result of high debt, low demand for its products (due to the pandemic) as well as depressed oil prices. Having significantly underperformed its peer group, ExxonMobil was a target for shareholder activists.

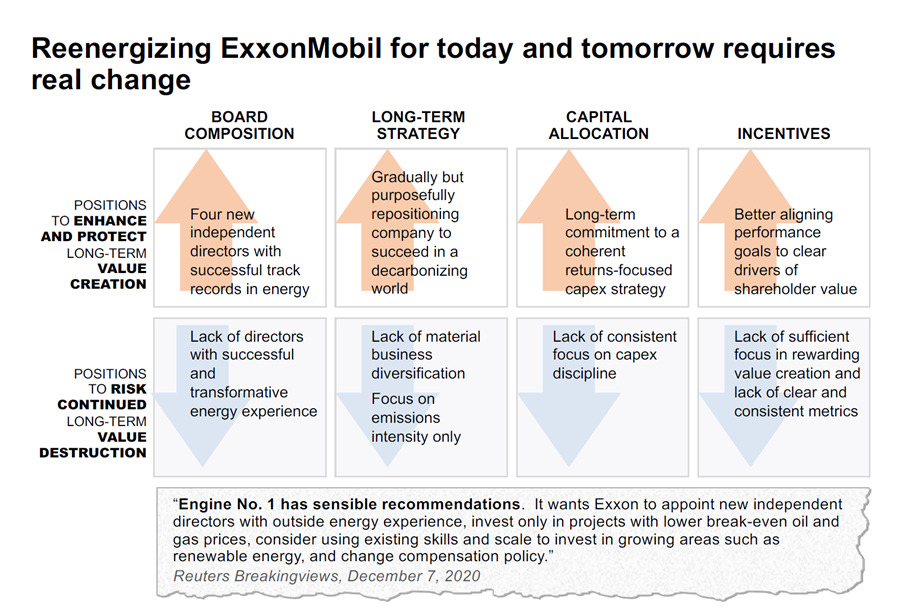

In its May 2021 investor presentation, Engine No. 1 seek to agitate for change via the nomination of four new independent directors to the board.

It succeeded.

In an interview explaining the victory, Wharton management professor Witold Heinsz, who served as a consultant to Engine No. 1, pointed out that “Engine No. 1 didn’t run its challenge to ExxonMobil as a green campaign, but as one that equated climate risk with financial risk in terms of how it destroys shareholder value”.

However not everyone was convinced this was a real victory for climate change.

Understanding Hedge Fund Activism

Bernard Sharfman, senior corporate governance fellow at the RealClearFoundation, a US non-profit investigative journalism organisation, described the proxy fight as “The illusion of Success”.

“There is no evidence that Engine No. 1 has served as a corrective mechanism (mitigating managerial inefficiencies) at ExxonMobil consistent with the theory of hedge fund activism”, says Sharfman in his submission published on SSRN.

Sharfman went on to assert that the only positive result was that Engine No. 1 obtained a “huge marketing boost in its efforts to raise funds for its exchanged traded funds (ETFs)”.

Drawing on the theory of the “Market for Corporate Control” by the late Professor Henry Manne, “hedge fund activism increases the wealth of shareholders and improves the performance of the public companies it targets”, with the change in stock price deemed the only objective measurement.

Source: Page 18 of Engine No. 1 Investor Presentation (May 2021)

Engine No. 1’s recommendations, as detailed in its investor presentation (excerpt above), lacked a great deal of specificity and suggested its ignorance of ExxonMobil’s operations or the know-how in managing the oil giant’s long-term future, argued Sharfman.

On that basis, the concept of “correcting managerial inefficiencies”, which should lead to increase of profits and share price, cannot be established.

Interestingly, when the activism became public in early 2021, ExxonMobil’s share price did rise.

However, according to academics Desai, Rajagopal and Tomar, this rise in stock price can be “attributed to a rise in oil prices that have benefited all oil and gas companies. If the market thought Engine No. 1 was acting as a corrective mechanism, it certainly did not reveal it.”

Timing

The intriguing thing about this case is that Engine No. 1 managed to win the proxy fight, despite the absence of specific recommendations or a positive stock market reaction, not to mention its miniscule shareholding.

Sharfman attributed that to the exceptional timing of this undertaking.

Besides highlighting ExxonMobil’s poor financial performance, Sharfman postulated that Engine No.1 successfully appealed to the desire of the Big 3 investment advisers, who are keen to bolster their green credentials. Such a perception, he wrote, “is necessary in order to attract millennial investors”.

Hence he believed that “the Big 3 were arguably in a bind. They were under a lot of pressure to support Engine No. 1’s efforts or else they would be perceived as not walking the talk on climate change.”

Unintended Consequences

While Engine No. 1’s proxy victory against ExxonMobil was a win for ESG activism, Sharfman was adamant that “characterising Engine No. 1’s victory as a win for climate action is akin to greenwashing when the concrete actions that oil and gas firms must take to transition sustainably, both from a financial and environmental perspective, remain elusive”.

Taking this further, this action may arguably be deemed as an impediment to the systemic issues that governments need to address to mitigate climate change. Tariq Fancy, BlackRock’s former Chief Investment Officer for sustainability investing, refers to them as “deadly distractions” or “social placebos”.

As a result of Engine No. 1’s activism, ExxonMobil will likely divest or reduce their investments in future oil and gas opportunities. However, there’s no stopping other private or national companies from venturing into such projects, with no accountability of their sustainability credentials.

Conclusion

Sharfman admitted that he did not have access to the Big 3’s stewardship teams or any inside knowledge of their decision-making process, although he backed his assumptions as being quite plausible.

Engine No. 1, on the other hand, may have benefitted from an increased profile among investors, enhancing the capital raising ability for its ETF funds. After the conclusion of the proxy fight, it announced the launch of its first ETF, Engine No. 1 Transform 500 ETF (ticker symbol “VOTE”), focusing on shareholder activism.

There are plans to launch another ETF, “The Transform Climate ETF”, focusing on climate change activism.

Marketing allegations aside, Sharfman emphasised that Engine No. 1’s proxy fight had done little for climate change.

More crucially, he warned that “it created a deadly distraction in our fight against climate change, a fight that should be taken on by governments all over the world, not hedge fund activists”.

Click here to download Bernard S. Sharfman’s paper on SSRN: “The Illusion of Success: A Critique of Engine No. 1’s Proxy Fight at ExxonMobil”