This month, I’ll dig into the real reasons why active management so often fails to deliver on its promises.

As a recap, in last month’s column, I wrote about nine common arguments in favour of indexing. These arguments either don’t stack up under scrutiny or apply in some circumstances but not others. I included a further four arguments in my bonus post.

There’s something for everyone in this post. Readers who believe in indexing will find a list of arguments supporting their conclusion. Meanwhile, active investors shouldn’t see this post as a list of negatives. Instead, they can use the points listed below as a checklist for improving their chances of success.

For those that can’t be bothered reading on, here’s a spoiler: The problem lies with the business of active investing, not the activity. It is definitely possible to beat the market. But for that to happen, investors must avoid common mistakes, such as those featured in this post.

Active management can be fixed, but it requires the joint effort of investment committees, internal teams, fund managers and consultants. Charley Ellis makes this very clear in his excellent paper: Murder on the Orient Express: The Mystery of Underperformance.

The final part of this series, part 3, will cover the strongest arguments in favour of indexing. So here are eight reasons why active management often disappoints.

1. Fund managers prioritising liquidity, capacity, career risk and management fees over performance.

Active management is a business. Consequently, the primary focus of the fund manager has to be on making a profit. Profitability depends on four things:

- Selling the client what they want. Usually whichever asset class or investment strategy that has recently performed strongly.

- Clients often prefer the complex over the simple and they have a bias to activity.

- Client retention. This usually requires avoiding unexpected surprises such as high levels of volatility or performance that deviates widely from the benchmark.

- Maximising the number of clients. Portfolios that are liquid and easy to trade allow the fund manager to increase the capacity of their strategies.

The first point guarantees that the client is likely to behave pro-cyclically. In other words, they will be on the wrong side of mean reversion most of the time. For example, “active extension” or 130:30 long/short strategies were very popular back in the mid-to-late-2000s when I began my career in institutional investing. These strategies offered by managers that had, up to this point, only managed long-only portfolios. They achieved widespread acceptance – just in time to be wiped out by the global financial crisis.

The second point creates an incentive for a fund manager to justify their fees by “doing something”, even if this comes at the expense of higher transaction costs and taxes.

The third and fourth points incentivise the manager to “closet index”, i.e. stick closely to their benchmark. This reduces tracking error (or variability of outcomes relative to the benchmark) and maximises liquidity and capacity. It also constrains the manager’s potential to beat the market.

How many good ideas can a fund manager have? A typical sell-side analyst will cover 10-15 stocks in detail. Most buy-side analysts will cover 20-30 in detail, while maintaining a watch list containing many more.

It’s reasonable to expect that not all of the stocks covered will be suitable for investment at a given time. Let’s assume, that a fund manager has a team of five analysts each covering 20 stocks. The manager wants to create a portfolio using the “best” ideas of each analyst. Picking the top 3-6 ideas from each analyst will result in a portfolio of between 15-30 stocks.

So why do so many fund managers run portfolios containing 50, 75 or even 100 or more stocks? Owning 70 stocks means that you’re investing money into your 70th best idea, instead of investing more money into one of your top 10 best ideas. How can that ever lead to out-performance?

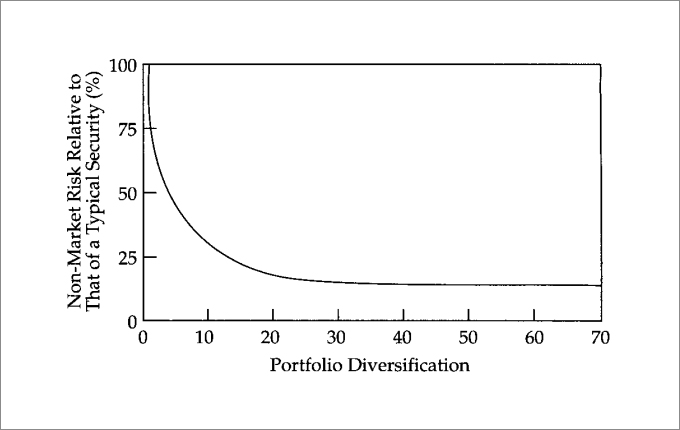

From an absolute risk perspective, there is no need to hold more that 20-30 stocks. Professor William Sharpe demonstrated that a portfolio of 10 stocks eliminates approximately 75 per cent of the risk of holding a single stock, while 20 stocks eliminates approximately 90 per cent of the risk.

The primary reasons why a fundamental manager would own more stocks is to ensure liquidity, maximise capacity, reduce peer risk and therefore maximise profits.

2. Genuine active management is A LOT more capacity constrained that most investors realise.

It doesn’t pay a fund manager to look for weak competition. Fund managers increase their odds of beating the market by focusing on areas where competition from other active investors is weak. An example is micro cap stocks. Institutional investors are less likely to invest in micro caps for reasons including:

- Size – It is difficult to own a substantial position without having to file a regulatory notice.

- Liquidity – A small free float and low trading volumes make trading difficult and expensive.

- Research – A lack of interest by fund managers means that there is little or no sell-side research coverage.

- Relative Performance – There can be very large differences in relative performance between micro caps and large cap stocks.

These factors make micro cap investing an attractive active investment opportunity. But they also limit capacity to such an extent that all but the smallest boutique fund managers are unlikely to launch a micro cap strategy.

Many institutional investors are becoming too big to benefit from active management. Let’s assume that an institutional investor, such as a pension fund adopts a policy of investing a minimum of 1 per cent of the total fund in a given fund manager. This helps to ensure that the pension fund’s investments make a meaningful contribution to overall fund performance. It also ensures that the time and attention of trustees and staff aren’t spread too thinly.

What happens when this fund reaches $50 billion in size? A 1 per cent commitment equals $500 million. The size of this commitment rules out effectively investing in capacity constrained opportunities for 3 reasons:

- $500 million is simply too much relative to the size of the opportunity.

- Fund managers will be unwilling to take the risk of most or all of their available capacity being taken up by a single client.

- Even if you do invest, it’s unlikely that a 1 per cent allocation will make a meaningful difference to the overall return.

The other alternative is to make smaller allocations. But this also creates problems:

- More allocations create the need to find even more high-quality fund managers.

- Interaction (e.g. redundancy) effects between fund managers are highly likely to dilute active returns but not management fees.

- Fund governance becomes more complex.

Investor time horizons are too short.

Investors underestimate how much patience they’ll need. Active management takes time to bear fruit. It may not work in the short term and it will not work year-in, year-out. The only way it works is if you stick with it. This is actually a good thing. Periods of under-performance refresh the opportunity set for an active strategy (see part one of this series).

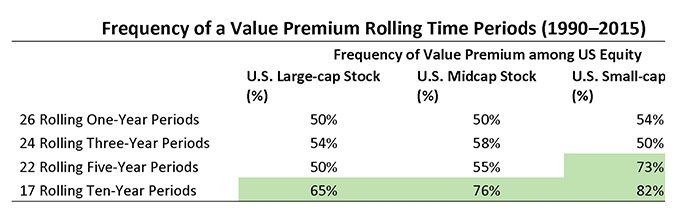

But just how long might an investor have to wait? It may take up to 10 years for an investor to be reasonably confident that active management will out-perform the market. Take value for example. In their paper, Comparing the results of value and growth stock market indexes, Fidelity examines the performance of growth and value indices in the US to their market capitalisation-weighted counterparts over the period from 1990–2015.

They found that over this period, investors needed to wait patiently for at least 10 years before the value benchmark beats its market cap counterpart at least two thirds of the time. Whether or not value out-performed the market over shorter periods was a roughly 50:50 proposition. In other words, it was little better than random.

Investors shorten their horizon by obsessing over short-term performance. Investors routinely shorten their investment horizon by monitoring performance over intervals that are far too short. This is a bad idea for two main reasons:

- The results are dominated by noise over short time periods

- We are prone to over-reacting to noise due to our behavioural biases

The probability that an investor will see a gain on their stock portfolio if they wait:

- 1 hour is approximately 50 per cent

- 1 day is approximately 51 per cent

- 1 week is approximately 53 per cent

- 1 year is approximately 73 per cent

- 10 years is approximately 100 per cent

Clearly, noise dominates for periods shorter than one year. In other words, we are just as likely to see a loss as we are to see a gain over periods shorter than one year. Prospect theory teaches us that most people hate losing money twice as much as they enjoy making it. Combine these two facts together and it’s not hard to see how frequently checking performance makes it feel as if active investing is riskier, shortening our investment time horizon.

4. A LONG chain of principal and agent relationships.

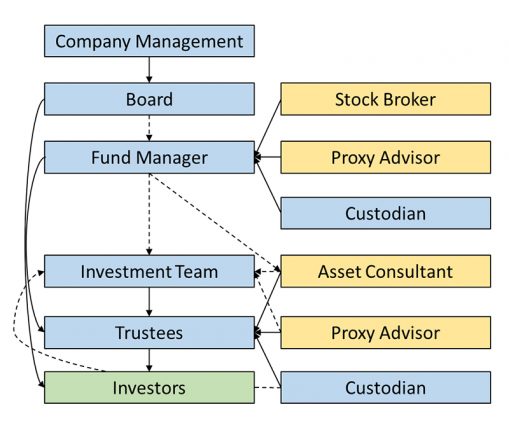

Ultimately everybody is an agent. Referring to institutional investors as “asset owners” is a pet peeve of mine. The only person that is a principal (acting for themselves) is the end investor. Everyone else is an agent (acting on behalf of someone else).

Agents have competing priorities: the responsibility to act in the best interests of their clients and the need to run a profitable business. This is known as the principal and agent problem (see my earlier post).

The more agents there are in the principal-agent chain, the greater the likelihood that the interests of the beneficial owner and each of the individual agents will diverge. Worse still, the potential impact isn’t additive, its multiplicative. Logically this has to have a negative impact investment performance.

Just how long is the chain of principal and agent relationships for unitholders in a typical investment product, such as a pension fund? The diagram below illustrates a stylised principal and agent chain, beginning with company management and ending with the investor or beneficial owner.

The investor is the only true principal (green) in this chain. All of the other nodes are agents, some with a fiduciary duty (blue) and some without (orange). Direct reporting lines are indicated by solid lines, while indirect reporting lines are shown with dotted lines.

The diagram only shows the agents that are directly involved in the investment process. It ignores other parties that also have a big influence the way funds are invested, for example: regulators, index providers, the tax office and performance surveys.

The diagram above highlights just how many opportunities there are for the priorities of agents and principals to come into conflict.

5. Incentives are all wrong. Who captures the value of active management?

Fund managers capture most of the expected benefits of active management. I examine the reasons why in detail in these posts:

Fund managers are incentivised to gather assets. They do this because it makes their business more profitable, even though they know that it comes at the expense of performance. Perhaps the best way to make this clear is with a real-life example.

I recently came across a Bloomberg article on the departure of Peter Kraus as Chief Executive Officer of Alliance Bernstein entitled: AXA Kills the Messenger. Apparently, Kraus made the mistake of publicly acknowledging that the active fund management industry had become too big and probably needed to shrink assets under management by “20-30 per cent”.

The decision of AXA, which is the parent company of Alliance Bernstein, is particularly puzzling because Kraus understood the problem and had a credible plan to address it. Kraus told Bloomberg last year that: “It’s pretty clear that active managers have not performed above their benchmarks in any great degree, and we as an industry really have to take a look at that and say: ‘What are we doing that’s not fitting the bill?'”

You can watch the interview where Kraus discusses the problems and the solution for active management here.

6. Clients paying fund managers for risk management.

Please see my earlier post where I describe in detail Professor Bruce Greenwald’s lesson on risk management from the Columbia Business School Value investing Program.

7. Fund managers doing dumb things to impress consultants: style neutrality, forecasting, valuation models, target prices, et cetera.

Fund managers design products to appeal to consultants. Consultants often act as gatekeepers between the fund manager and client, creating an incentive to impress the consultant. Fund managers do this by focusing on the concrete aspects of their process, such as proprietary valuation models. Contrast this with how Charlie Munger and Warren Buffett approach selecting their investments:

“Warren talks about these discounted cash flows. I’ve never seen him do one,” Munger said.

“It’s true,” replied Buffett. “If (the value of a company) doesn’t just scream out at you, it’s too close.”

Or Buffett’s comments on the folly of target prices. For example,in his 1995 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, Buffett wrote about his experiences with Disney:

“I first became interested in Disney in 1966, when its market valuation was less than $90 million, even though the company had earned around $21 million pre-tax in 1965 and was sitting with more cash than debt… Duly impressed the Buffett Partnership Ltd. bought a significant amount of Disney stock at a split-adjusted price of 31 cents a share. That decision may appear brilliant, given that the stock now sells for $66. But your Chairman was up to the task of nullifying it: in 1967 I sold out at 48 cents.”

Buffett sold Disney for a quick 55 per cent when it reached his target price, only to miss out on a 21,290 per cent gain (not counting dividends)!

Style neutrality increases the capacity of a strategy (point 1) and also reduces the chances of a nasty surprise, especially over the short-term (points 1, 3, 6 and 8). Nobody, not the fund manager, the consultant, the internal team or the investment committee want this. Each agent has their own incentives to avoid short-term underperformance.

The emphasis is usually on products that will sell, products that are safe to recommend, that feel comfortable to own, but not products that will perform.

Reminds me of a joke about a fisherman who walks into a bait and tackle shop searching for a lure. He finds an aisle stacked full of brightly coloured lures of all shapes and sizes. Confused, he decides to ask the shop assistant for help:

“Excuse me, do fish really like these brightly coloured lures?”

To which the shop assistant replies:

“I don’t know, I’ve never sold a lure to a fish before.”

8. Following the advice of a consultant.

How do you select a consultant? If you don’t trust yourself to pick a stock, then what makes you think you can choose a fund manager? And if you don’t trust yourself to choose a fund manager, what makes you think you’ll be any better at selecting a consultant?

When you think of it this way, the idea of hiring a consultant makes little sense. How can you ever know if the advice you receive is appropriate for you?

Aren’t they supposed to be the experts? Yes, many consultants are skilled and experienced. But we must remember that consultants, just like fund managers, are running a business. David Swensen Chief Investment Officer of the Yale University endowment explains the implications in his book Pioneering Portfolio Management: An Unconventional Approach to Institutional Investment.

“Consulting firms maximise profits by providing identical advice to as many clients as possible. In the investment world, which demands portfolios custom tailored to institution-specific risk and return preferences, a cookie cutter approach fails …

… Interposing consultants between fund fiduciaries and external managers creates a range of problems that stem from a disconnect between the consulting firm’s profit motive and the client’s investment objectives. While consulting firms offer a shortcut that avoids the hard work of creating a dedicated investment operation, as is the case with many shortcuts, the end results disappoint.”

Selling opinions is a tough gig. What happens if a fund manager recommended by a consultant performs poorly? The client loses money but the consultant doesn’t. They have no skin in the game.

The lack of any genuine skin in the game also means that there is no upside for better than expected performance. Most consultants work on a fixed retainer plus occasional payments for special projects not covered by the retainer. It makes no difference if they help the clients beat the market, but it makes a lot of difference if they underperform.

What the consultant loses is their reputation. A consultant can only suffer so many hits to their reputation before their expertise is called into question by the client. In other words, a consultant is more concerned about reputational loss than a direct financial loss.

The quote by Swensen alludes to the fact that consulting is a scale business, where profitability is only achieved once the high fixed costs of research are spread across multiple clients. Acquiring new clients is difficult as clients don’t change consultants often. Also, industry consolidation means that the list of potential clients is shortening. The harder it becomes to gain a client, the stronger the incentive not to lose one.

Furthermore, consultants have no control over how their advice will be implemented by a client. For example, a client may recommend a fund manager, but the client may decide to invest in that manager several months later following a period of very strong performance. The client also decides to invest a larger amount. Once the client invests, the fund manager performs poorly. Was the consultant wrong? No, but they will probably be blamed for the client’s timing and allocation mistakes.

What would you do if you were in this situation? Again, Swensen gives a perfect description of what happens.

“Selecting managers from the consultant’s internally approved recommended list serves as a poor starting point for identifying managers likely to provide strong future results. No consultant who wishes to stay employed recommends a start-up manager with all of the attendant organisational and investment risks. Because consultants seek to spread the costs of identifying and monitoring managers, consultants recommend established managers that have the capacity (if not the ability) to manage large pools of assets. Clients end up with bloated, fee-driven investment management businesses instead of nimble return-oriented entrepreneurial firms.”

A consultant’s job is to help you do what you were already going to do in the first place. If we accept that consultants are incentivised to keep their clients happy and avoid embarrassment, then we shouldn’t be surprised by what follows next according to Swensen:

“Consultants express conventional views and make safe recommendations. Because consultants rarely espouse unconventional points of view, they provide more than adequate cover when dealing with investment committees. Decision makers rest comfortably, knowing that a recognized consulting firm blessed the chosen investment strategy.”

So that’s it, eight reasons why active management often disappoints. Remember none of the reasons above are set in stone. Fund managers, consultants, investment teams and investment committees can work together to fix the situation.

But unless they do, most of us are probably better off indexing. The final part of this series, part 3, will cover the strongest arguments in favour of indexing.

Follow the Market Fox – Blog: www.marketfox.org or on Twitter: @market_fox.

__________

[i3] Insights is the official educational bulletin of the Investment Innovation Institute [i3]. It covers major trends and innovations in institutional investing, providing independent and thought-provoking content about pension funds, insurance companies and sovereign wealth funds across the globe.